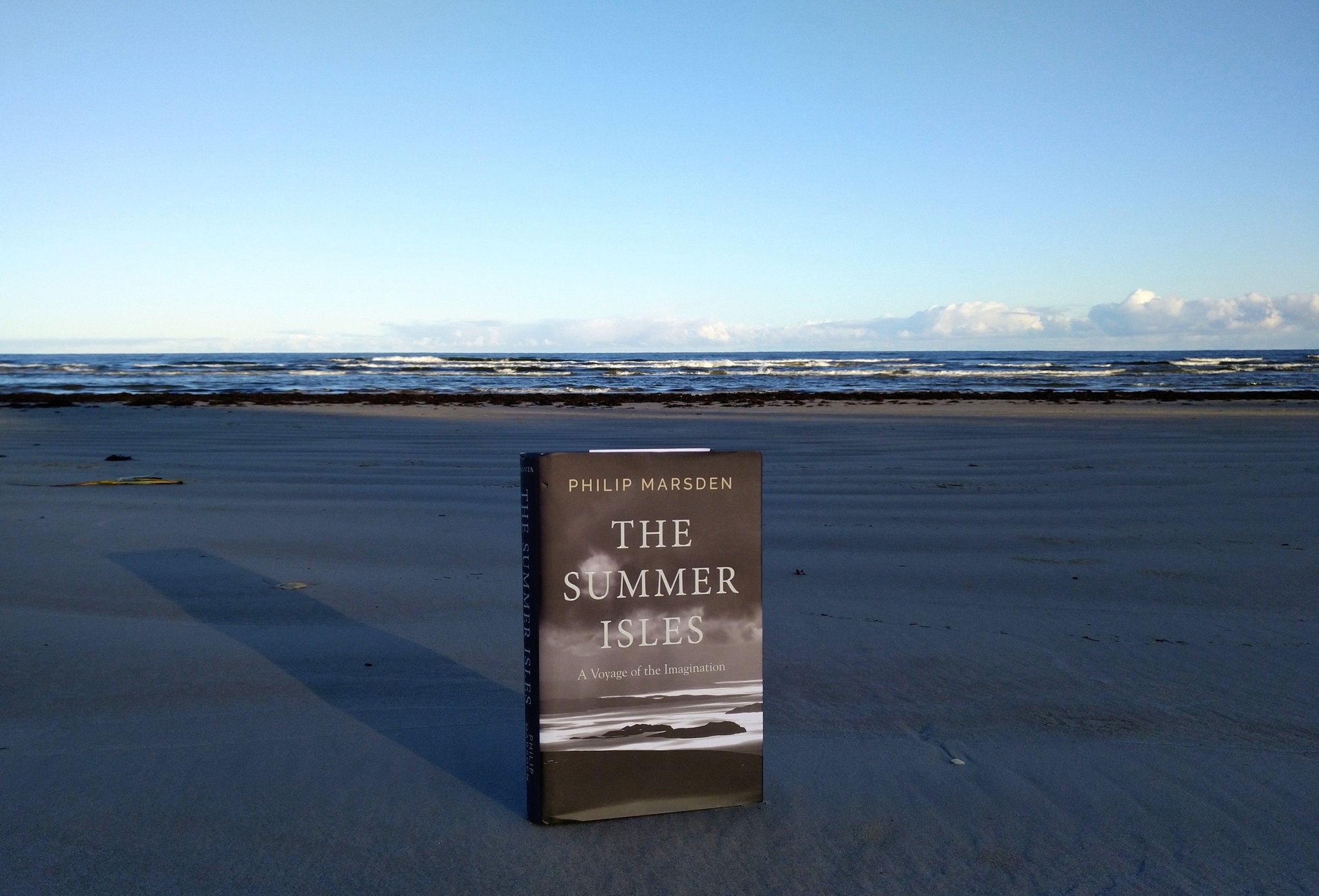

“This book is about such places – places drawn by longing and memory, places just beyond our reach, places that aren’t really there at all – and it’s about what happens when you set sail in search for them,” writes Philip Marsden in the first chapter of his new book The Summer Isles: A Voyage of the Imagination, published this autumn. In the book the author sets sail along the West coasts of Ireland and Scotland, island-hopping in the Atlantic Ocean and in the seas of our imagination. He sails single-handedly for the first time in his life in a wooden boat Tsambika.

Philip Marsden is an award-winning English travel writer and novelist, living in Cornwall with his family, where they have planted four thousand oak trees. He has written ten books, including Rising Ground: A Search for the Spirit of Place (2014), The Levelling Sea: The Story of a Cornish Haven in the Age of Sail (2002) and novel The Main Cages (2002) which is set in Cornwall in the mid 1930s.

“Of all environments, it is the sea that has the greatest ability to transform – as the crumbler of coastlines or the great driver of the world’s climate, as much as the conduit for our own restless hopes,” you can read in The Summer Isles. “The sea enables and it destroys. It is a constant reminder that we are powerless beside the forces of nature – and that what we feel as firm beneath our feet is not solid. If terrestrial journeys are simple trials of the body, then a sea journey is a passage of the soul.”

The Summer Isles is a book about islands, real and imagined. Why do we need islands, and those we will never really reach?

I’m not sure we need islands as such, but we do seem to need somewhere physical to try and fix our loftier notions, our wild hopes and aspirations, our imaginative flights. There are traditions everywhere of projecting such things on the land around us – yearning for distant mountains, attaching stories of gods and heroes to prominent hills, siting elaborate myths in lakes and caves. But of all topographic features it is islands that have always drawn the greatest number of stories and ideas. Somewhere discrete, self-contained, lying off the mainland, somewhere visible but chimeric, or somewhere believed in or rumoured to exist just over the horizon is the perfect embodiment of our ideals.

Alberto Manguel’s Dictionary of Imagined Places is a compendium of 1200 places gathered from various canons – from Atlantis to the Fortunate Isles, from Hogwarts to Middle Earth. Far and away the most common form of the imagined place is islands. When it comes to islands, we are at our most credulous – made-up islands have seeped back into our perceptions of the real world. For centuries Europeans were convinced about Atlantic islands like Antillia or Hy-Brasil. Their names crop up on late medieval charts and portolans of the Atlantic, even into the nineteenth century. Countless ships went off in search of them. But they never existed.

As for reaching them or not, it is in the nature of myth-rich places that they should remain just out of reach. Much as we would like to unite the physical and the metaphysical they remain forever separate. What happens when we get to longed-for places? We wander about a bit, we set expectation against reality, we feel disappointment – then we go off and look for somewhere else. Oscar Wilde wrote: ‘A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail.’

The voyage along the West Coast of Ireland and Scotland was your first experience as a single-handed sailor. Why did you choose to sail alone and how was it?

I’ve written a number of travel books – about land-based journeys in the Middle East, the Caucasus and Ethiopia. I believe strongly in the narrative power of the travelogue. On those journeys, I learnt the advantage of travelling alone, the joys of following your own nose, letting stories take you where they will, and the rewards of anonymity. Alone, you become more responsive to the pull of the world, less wilful. You are more open to impressions alone, more receptive. You are also more likely to meet people, and they’re more likely to open up – possibly because they feel a little bit sorry for you.

The Summer Isles is essentially a travel book and, in the cosy study-warmth of its conception, I naturally adopted the lone-traveller method. What I hadn’t factored in was that single-handed sailing is a little different from jumping on and off a bus or walking from village to village. If I had, then I probably wouldn’t have done it like that, but the result would have been much less interesting. I’m an experienced day-sailor, and had done a fair amount of cruising on other people’s boats. But being on your own, and choosing as my first outing the west coast of Ireland was challenging, to say the least. Exposed to the Atlantic, with long stretches lacking decent harbours, it was a crash-course in single-handed sailing. The boat was well set up – with halyards leading back to the cockpit. But there were constraints, particularly when things went wrong. Good seamanship is about anticipating hazards, preparing for what-ifs. I did plenty of that but there were countless times when another pair of hands would have made things a whole lot easier. But on the other hand, the whole experience was extraordinary. I wouldn’t have changed it for the world.

Tsambika is a strong character in your book. You often write ‘we’. Tell me about your relationship with the beautiful wooden boat.

I hadn’t really noticed that ‘we’ until it was pointed out. I don’t hold much truck with animating what is essentially some pieces of dead wood fixed together into a vessel. That said, a boat does hold many of the attributes of, say, a horse – the way it moves in a stormy sea, the demands it makes on you in tethering it properly, in caring for it, and the immense strength and power that it offers. And there were times at sea, when Tsambika rode some vast swell or dipped her gunwale to the wind, when she appeared to be alive, making choices, responding. Conrad thought the regard that mariners have for their boats is ‘profoundly different from the love that men feel for every other work of their hands’.

Throughout The Summer Isles you have mixed feelings about being at sea. Fear and excitement to leave the coast, longing for land and ‘normality’ and for the adventure of the open sea. Why do you love sailing despite the dangers of the sea?

The danger of course is part of the appeal, not out of some perverse death-wish but because any sort of elemental challenge sharpens the senses, as well as the creative faculties. I think back to that time along the west coasts of Ireland and Scotland as some of the most intensely-felt months in my life. But I know too that they were accompanied by a constant low-level anxiety, punctuated by moments of outright fear. Such sustained exposure to the forces of the natural world is good for the soul. The rewards of sailing for me are not so much the sailing itself, the seafaring, as the sights it allows you, the places you manage to reach, the evenings spent in small anchorages with just the seabirds and seal-sounds, or the encounters with people that you’d never have met if you hadn’t arrived alone in a small wooden boat.

Which books did you have with you on Tsambika? How did they shape your voyage?

I had pilot books, books of navigation, manuals of engine maintenance, almanacs filled with tide tables and tidal graphs and these were pored over as much as anything in my onboard library. But for contemplative pleasure I carried in the shelves (with their removable brass-tipped bars to stop the books spilling out) any number of old favourites, as well as books of local history and lore picked up en route. Staples were Irish heroes like Yeats and Heaney, Kavanagh and Flann O’Brien, and a few maritime classics like those of Jonathan Raban and Herman Melville. I had various translations of the early Irish voyage tales, the immrama and echtrai, of Bran and Brendan – and the Táin Bó Cúailnge and Jeffrey Gantz’s Early Irish Myths and Sagas and JG Campbell’s The Gaelic Otherworld. Also a good store of fat novels.

Something in the nature of the voyage, the constant need for vigilance meant that full immersion in books was not always possible. So there was a fair amount of ‘snacking’ – grabbing a few pages here and there before I had to fix something or tend to the sails or anchor, or simply to stick my head out of the hatch and have a good look around. I have to say that one of the great joys of the journey was sitting down below with the lamps lit and the weather raging outside, reading. That was where much of the non-sailing parts of the book found their shape.

Stories about the islanders are partly stories about the past. What, in your opinion, will happen to the life on Irish and Scottish islands in future?

One of the themes that arose from the journey was the way that the past is contained in these rocky western coastlines, the way we project our nostalgic notions upon them, looking for traces of something that elsewhere has been snuffed out by the winds of progress. I became intrigued by that newly-emerged branch of psychology, ‘nostalgia studies’ in which nostalgia is examined under clinical conditions for its physiological effects. Rather than something reactionary and escapist, the tendency towards nostalgic thinking has been identified by many psychologists as an essential part of our mental processing.

The reality of life on those islands of course is very different – a harsh and marginal existence. A recurring image I had from the boat was of roofless gables on the skyline of abandoned islands. Over the last couple of centuries, the populations have fallen steadily. In many cases – the Blasket, the Inishkeas, Inishark and St Kilda – they reached a tipping point and the remaining people left en masse. As for the future, life is bound to remain difficult and hard-won. Even with communications being what they are, the sense of isolation on the periphery has become magnified in recent decades. The continuing appeal of such coasts – the success in Ireland of the Wild Atlantic Way or in Scotland of the North Coast 500 – shows that there is a future in the tourist economy – fickle though the tourist dollar is. There’s the on-going debate about fish-farming – the terrible damage they do to the marine environment versus the local jobs they support. Farming in marginal areas is also threatened by industrial farming elsewhere. It is not easy to see a course through all these hazards. What is needed is a serious valuing of such communities, their traditions and the delicate ecology in which they exist.

What a marvellous interview, and what beautiful, rich and evocative language Philip Marsden uses. Fascinating to hear the new thinking on the value of nostalgia. Now on to The Summer Isles……

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you and yes, I agree… do read the book, it’s marvellous!

LikeLike