This material first appeared on the Library Portal on July 19, 2022, in Latvian. I interviewed Katie Patterson and Anne Beate Hovind as an editor of the media, which is run by the Library Development Centre at the National Library of Latvia. For the material to be available in English as well, I’m re-posting it on the Sea Library’s website.

Going to the library to read books written one hundred years ago and even earlier than that is a common thing. The special ability of a word captured on paper is to travel through time. The work of memory institutions – libraries, museums, archives – is to keep what has been created safe and available to future generations. Thanks to this, long after the death of the authors and their fellow human beings, the cultural heritage lives on.

But what if the library would house the artifacts of the future? What if the library would be like a time capsule, allowed to be opened only after a century? A library that would store manuscripts that will only be read by people of the future? All of the above has been realized by the Scottish artist Katie Patterson. In collaboration with the City of Oslo and the Oslo Public Library, she has created the Future Library.

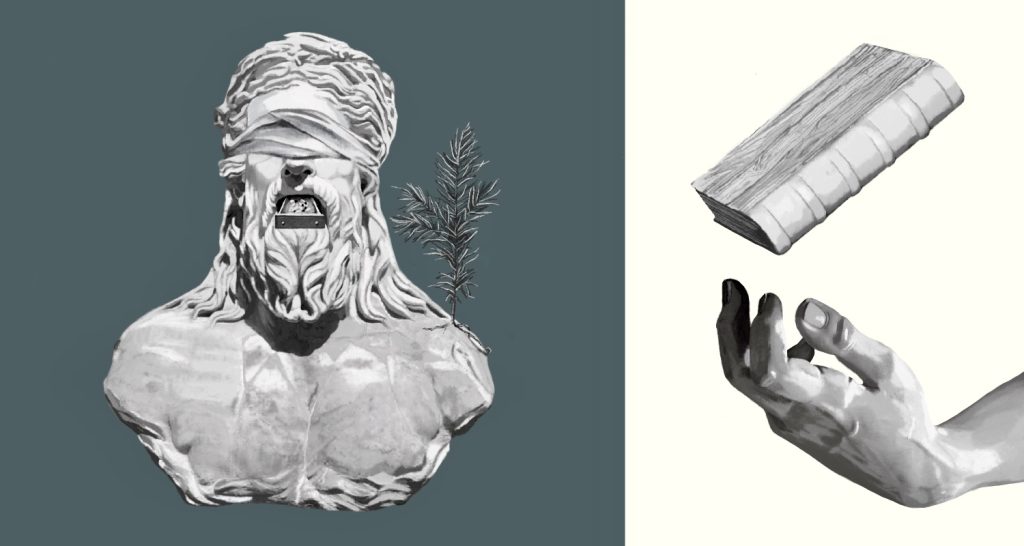

In 2014, in the Norwegian forest, on the outskirts of Oslo, the artist started a unique project, planting a spruce grove of one thousand saplings. A hundred years later, the paper will be made from them and a special anthology will be printed: one copy from each spruce. The anthology will consist of one hundred literary works, which will be written and deposited by both contemporary writers and those who have not yet been born. The book manuscripts will be readable only after 2114 when the project will be concluded and the time capsule will be unlocked. The British newspaper The Guardian has called the Future Library “the world’s most secret library” and the BBC – a library with “unreadable books”.

As an artist, Katie Patterson has always been interested in deep or geological time. One of her first works of art (Vatnajokull (the sound of) in 2007) was a telephone line on which you could call and listen to the melting of glaciers in Iceland (the telephone line was connected to a microphone submerged in water). The artist is interested in geology, astronomy, and mankind’s time on Earth. The idea for the Future Library came to her when she once sketched the connection between trees that form annual rings as they grow and books that are printed thanks to recycled wood. She instantly had a vision of a book growing with the trunk – chapter by chapter, ring by ring.

“The idea for Future Library happened in one of these moments where notions of time, growth, future, place, stories, pulp, matter, cells, smells, all collapsed into one,” the artist tells to the Library Portal. “This artwork brings together the work of preeminent writers, thinkers, and philosophers of this and future generations. It is an artwork that belongs not only to us and the City of Oslo now but to those who are not yet born.”

Although the books cannot be read yet, the Future Library itself can be visited today. Oslo’s public library Deichmann Bjørvika, which opened its doors in 2020 (and last year was recognized as the best in the world in an IFLA international competition), has a special Silent Room. It was officially opened this summer, on June 12. Eight manuscripts are kept in the Silent Room, the design of which was developed by the artist herself. Among them is the very first submitted work – by Margaret Atwood, and the manuscripts of Karl Ove Knausgård, Tsitsi Dangarembga, and Ocean Vuong, which were handed over in June. (With the pandemic, the celebratory annual handover was interrupted, and this summer there were already three works.) Each year, another will be added, waiting for the forest to grow strong.

Latvian Library Portal invited Katie Patterson, the author of the idea of the Future Library, to an interview to learn more about how such a special project was created. We also contacted the implementer and curator of the idea, Anne Beate Hovind from Norway, without whose work the Future Library would probably have remained only on paper. But first – a conversation with artist Katie Patterson about the present, future, nature, and, of course, libraries.

How did you come up with the idea of the Future Library?

Future Library is my most ambitious artwork to date. It has been several years in the making and it will outlive me and most of us alive today. It is a slow, evolving artwork that will unfold in Norway for over 100 years.

Future Library was a seed in my mind several years ago. I was extremely happy to be approached by Bjørvika Utvikling to work on a commission for Slow Space, a series of public artworks for Oslo. Norway felt like the perfect place for Future Library to exist and grow. Being covered by forest, with the city surrounded by trees, I imagined the forest may be part of people’s psyches in a more pronounced way. Perhaps a 100-year artwork might be received and thought about differently. Then Norway’s historical and contemporary literary connections, the connection with the new library, and the forward-looking views on nature and the environment. Everything fell together. I had a very clear vision for Future Library, but at that point, I could never have imagined it would go beyond the dreaming stage.

The idea to grow trees to print books arose for me through making a connection with tree rings to chapters – the material nature of paper, pulp, and books, and imagining the writer’s thoughts infusing themselves, ‘becoming’ the trees. Almost as if the trees absorb the writer’s words like air or water, and the tree rings become chapters, spaced out over the years to come. I wanted the Future Library forest to exist within a larger forest, becoming part of its ecosystem and becoming, perhaps, more expansive in the imagination. The forest we have planted is situated a 40-minute walk from a metro station in Oslo, yet feels deep within the forest. It has no city sounds. We planted 1,000 Norwegian Spruce trees which in 2114 time should print 1,000 anthologies.

What role does the 100-year-time-scale play?

Future Library unfolds over a century. It takes place over slow-time and embraces a deep time perspective. We commission a new author every year, we gather in the forest every spring, and the artwork unfolds at the pace of tree growth, with the changing seasons, not by the norms of a public-art commissioning timetable. I don’t think these time spans are new for us but perhaps lost or forgotten. 100 years is not very long. It is just beyond most of our life spans and so allows us to consider our own mortality, and to imagine all those unborn who will come after us alive now, and walk in the same footsteps. I believe we have to learn to see future generations and connect with them with just as much respect as to those living now. Expanding our time horizons to envisage a longer now is the most imperative journey any of us can make.

What are the challenges, of creating and sustaining the Future Library?

Planning Future Library has been a challenge in many ways: from the consideration of tree types, forested areas, Norwegian insects, and climate, to working with lawyers on 100-year contracts, selecting and inviting authors, thinking and developing artwork on a timespan that is new for me. Trust is a dominant concept throughout. Support has been given by the City of Oslo and we are working together to ensure the protection of the forest and manuscripts until 2114. We have formed the Future Library Trust, whose mandate is ‘to compassionately sustain Future Library for its 100-year duration.’

We are doing all we can to preserve the printed book on paper in 100 years’ time. We will leave specifications on how the books are to be made, and work with Norwegian paper using traditional and natural techniques to pulp trees and make paper. The anthology will be designed in advance, with instructions left behind. We will seek advice from the foresters as to how the trees will best be harvested. All of this will be passed down through the Trust when I am gone.

There are an unlimited set of possibilities of what might happen between now and the printing of the Future Library anthology. Norway as a country might not even exist. Tectonically, and topographically, the planet will be different, as the weather patterns shift and change. There are many unknowns: will an electrical storm wipe out the forest? Will the fjord have overtaken the land? And never mind the forest itself surviving, Margaret Atwood asks will human beings survive the 21st century?

A year after the Future Library project will be finished, in 2115, a movie created by John Malkovich and Robert Rodriguez and named “100 Years” will be premiered. Why do you think artists have a need to create something that won’t be seen by anyone alive today?

There is a term that I learned, ‘Cathedral Thinking’: large-scale, long-term approaches to space exploration, city planning, and other long-term goals that require decades of foresight. It is pertinent right now as the time-span people live by is reduced and reduced.

How you as an artist with an ego and as a curious human being deal with the impossibility to be there when the project will be finished and when the books will be printed and read? Have the writers expressed their own feelings to write for the future? For a future editor, for a future reader?

The different groups of people who are collaborating – the foresters, the Trustees, the librarians, the writers- it doesn’t matter to them they cannot read the book. What matters is now, building an artwork that unfolds through time into the future.

We are all in agreement that the only other people to read the texts will be the author’s editor or proofreader. The author’s name will be displayed in the library’s Silent Room, but nothing beyond that; this is where the imagination must journey to. I will definitely not read the manuscripts. Of course, it is incredibly tempting, but it would go against the ethos of the project, leaving these unread manuscripts for an unborn generation.

That the text is a secret is at the heart of Future Library. I feel entirely comfortable that I will never read them. This project does not pander to instant gratification. I like to accept that a huge span of time has to pass before the future reader can open the first page.

Margaret Atwood described the project as ‘a tribute to the written word, the material basis for the transmission of words through time – in this case, paper – and a proposal of writing itself as a time capsule since the author who marks the words down and the receiver of those words – the reader – are always separated by time.’ She says Future Library ‘will contain fragments of lives that were once lived, and that are now the past. But all writing is a method of preserving and transmitting the human voice. The marks of the writing, made by ink, printer ink, brush, stylus, chisel – lie inert, like the marks on a musical score, until a reader arrives to bring the voice back to life.’

I like very much Margaret Atwood’s description of the human voice being brought back to life. I believe that the manuscripts are carriers of voices, that resonate organically through the trees as they are grown. And carriers of languages, which now in the year 2020 we don’t know will exist when by the time the books are printed. As writer Sjón said, during the handover in the summer of 2017, ‘Icelandic is a minority language.’ Languages, like species, go extinct, and this project is one of preservation.

Tell me more about the concept and design of the Silent Room.

The room was right in the early stages. We met with Liv Saeteren, the previous director of the Oslo public library, who is on the Future Library Trust. And it was uncanny! Liv had actually had a vision herself – because they knew they were building a new library – of a room in it to hold unpublished texts. As time went on, it had disappeared from the plan, but they’d always kept a space in the architectural plans for this sort of the beginning of an idea, but it wasn’t a priority.

Then I came along and told her about the trees and the idea of growing this collection of unread books. And then I said: “We need to put the manuscripts somewhere, and could it be part of the library?” It was this extraordinary moment of serendipity. There was this little footprint in the floorplan ready for us to appear. Which is quite magical, I think. That’s how the room came about.

As to the actual design and building of the room, we cut the trees in the forest, in 2014, as part of the natural regeneration of the forest. We stored the wood since then, which has been dried and taken care of. And I worked with the architects of the library, Lundhagem, and Atelier Oslo to design this room that’s going to hold the manuscripts. I always knew it would be made from the wood that we’d cleared from the forest – I thought these trees have to be part of this project because we’re moving in on the forest space.

At the end of the interview, we also asked some questions to the curator of the Future Library and the implementer of urban art projects, Anne Beate Hovind. Anne’s answers came inspiringly slowly from a wild island in Norway where Anne had gone to enjoy the summer – without electricity.

What do you love the most about the Future Library?

What I love the most about the Future Library is that we managed to make it happen despite all obstacles. It has proven that magical things can happen if we put our will and effort into it. And what I also love as much is how it resonates with people from all over the world, across borders, languages, ethnicities, and religions. It is truly a bridging work. We couldn’t know this would happen. The outreach has been and still is overwhelming.

What is your recipe for a better future?

My recipe – if any – I’m trying my best to do good. We are facing so many challenges and uncertainties today with war, and climate change with all the effects it has on our lives. I believe in creating bridging works as Future Library which at its core has to do with basic human needs that we are in need of now: Rituals, hope, trust, and long-term thinking.

What role do libraries play in your life? Do you have your favorite library?

Libraries have always been important to me since I was a little girl growing up on a farm in the deep forest. We didn’t have books at the farm, but every Tuesday my mother took me and my sister to this small local library. She always borrowed a pile of books. The library was a gate to a different world, to the imagination, narratives, and new perspectives.

My favorite library today is the new public library Deichman Bjørvika in Oslo where the Silent Room is on the 5th floor. It has become the most vibrant, diverse, safe, and free public space in the city. It has truly become a library for everyone. Hanging out there is just wonderful and makes me truly hopeful for the future and the coming generations. I believe this role is very important. And a place and space for exchanging ideas, debate, and reflecting.

What would you want the libraries to be like after 100 years?

I want them to stay like this new library. Not just like it of course. It needs to develop and stay relevant to the people. But I want to be a place that protects and emphasizes freedom of speech and thoughts, respect, acceptance, and diversity. Democracy.

Interviewed by:

Anna Iltnere

Editor of Library Portal

Library Development Centre

The National Library of Latvia

anna.iltnere@lnb.lv