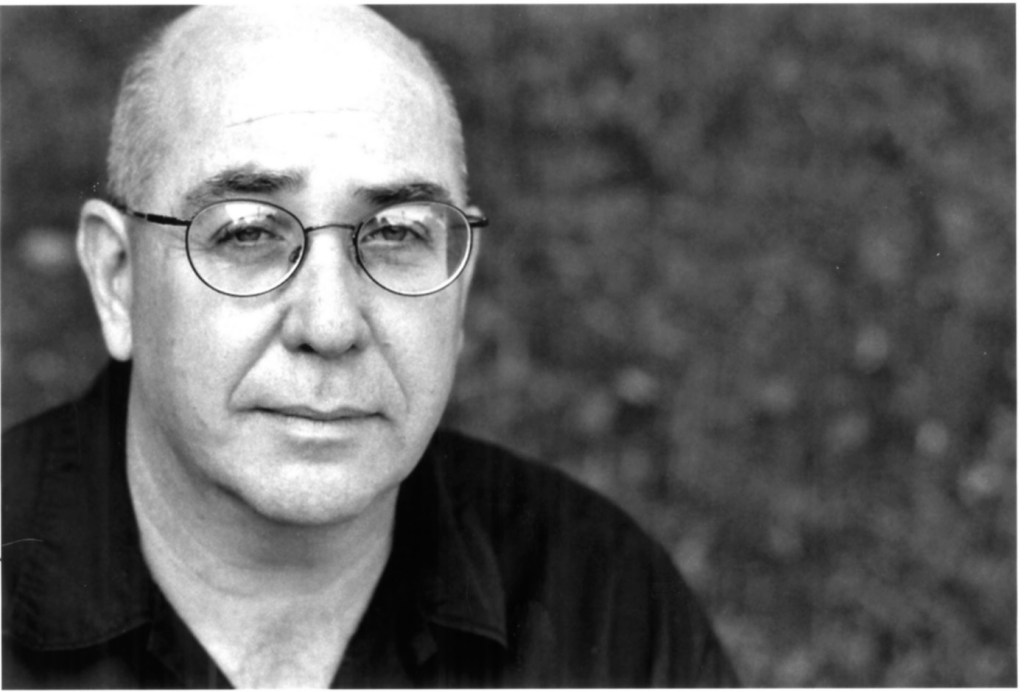

Introducing San Francisco writer Lewis Buzbee in a formal way feels almost impossible. He is one of the reasons I believe in magic realism—we first connected through Amazon reviews and have since written a manuscript together. A prolific author, his books, especially The Yellow-Lighted Bookshop, have profoundly shaped my life. More than anything, Lewis is my friend.

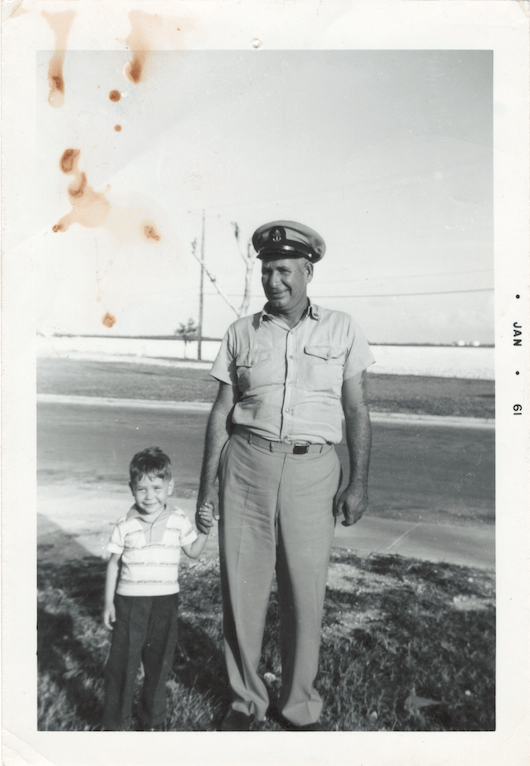

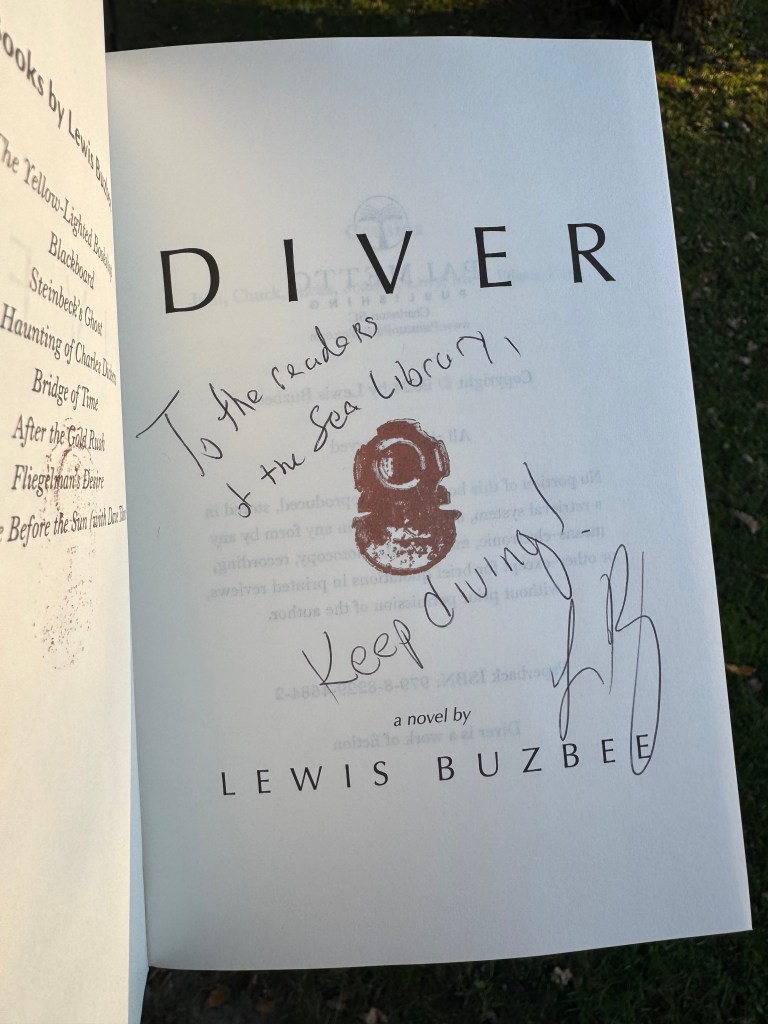

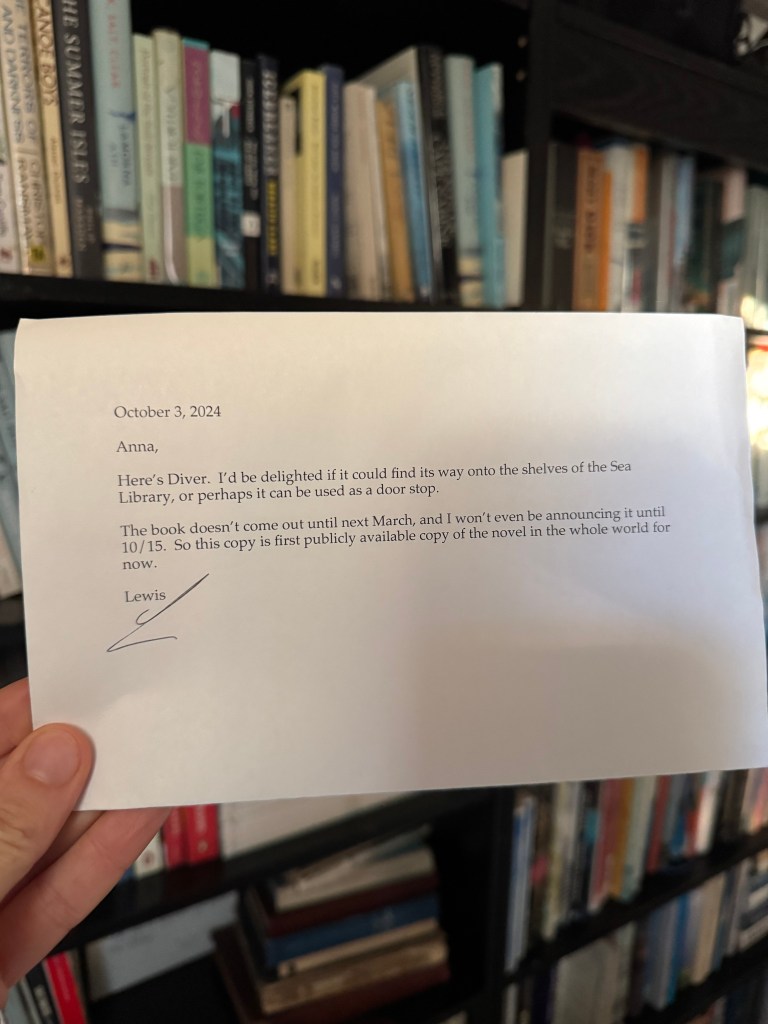

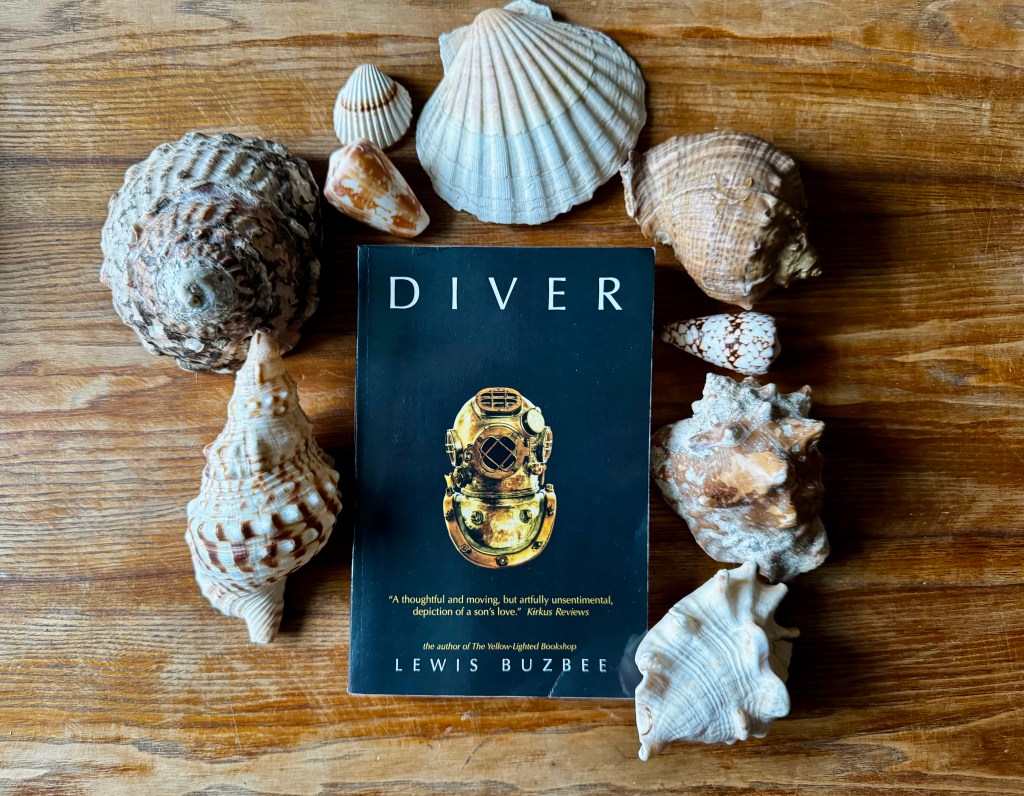

On March 3rd, his latest novel, Diver, was released. Deeply personal and beautifully inviting, it tells the story of a young boy navigating the loss of his father at just 12 years old. Inspired by Lewis’ own life, it is both a tribute to his father—a deep-sea diver—and a story that transcends memory, reaching into something larger than life.

“There were mornings on the water that I loved, placid surfaces waiting to be smashed. But it was afternoons on and near the water with my father that most occupied me, shards of light and motion bouncing in my head as I made my way through other days, walking home from school in the tree-shrouded autumn, or lying in the back seat of the car with the sky flashing orange through my eyelids, returning to those swells and shores. All those afternoons near the water, one once, one kaleidoscopic day, one long afternoon he and I shared basking.

Lakes and pools, a few rivers, but mostly the ocean. My family was never far from the ocean.”

Lewis Buzbee, Diver

Do you remember the day you began writing Diver?

Quite clearly. The first Covid lockdown had just begun, and I was sitting around one Saturday night, reading, and the sentence “I could not find him” popped into my head. Followed by a memory of my father, who died when I was 12, the memory of a night during a Boy Scout ski trip. We were staying in a large cabin, but I couldn’t find my father, so I went out into the snow and up the road to the main highway, where I found him sitting at the bar in a local tavern. I immediately went to my desk and “transcribed” this memory, 3 short pages. I had carried that memory since my father had died, but never wrote it down.

It was as if the gates of memory had opened wide, and the next night, unplanned, I wrote out a memory of my father and brother and I at a local beachside, the three of us—I’m only 12—running from the military shore patrol. Both my father and brother were military men. The next day I discovered that it was the 50th anniversary of the Kent State massacre, May 4th, 1970, when American soldiers killed 4 college students protesting the war in Vietnam. On that day, after our family watched the nightly news, my father had a heart attack and died. 50 years later, I wept like a child for my father, once again. After that, I just kept writing these, well, shards, I call them, and two years later I finished the first draft. I had never written a book like this, patiently and waiting for the memories.

I feel like this book holds a special place for you—it seems so important.

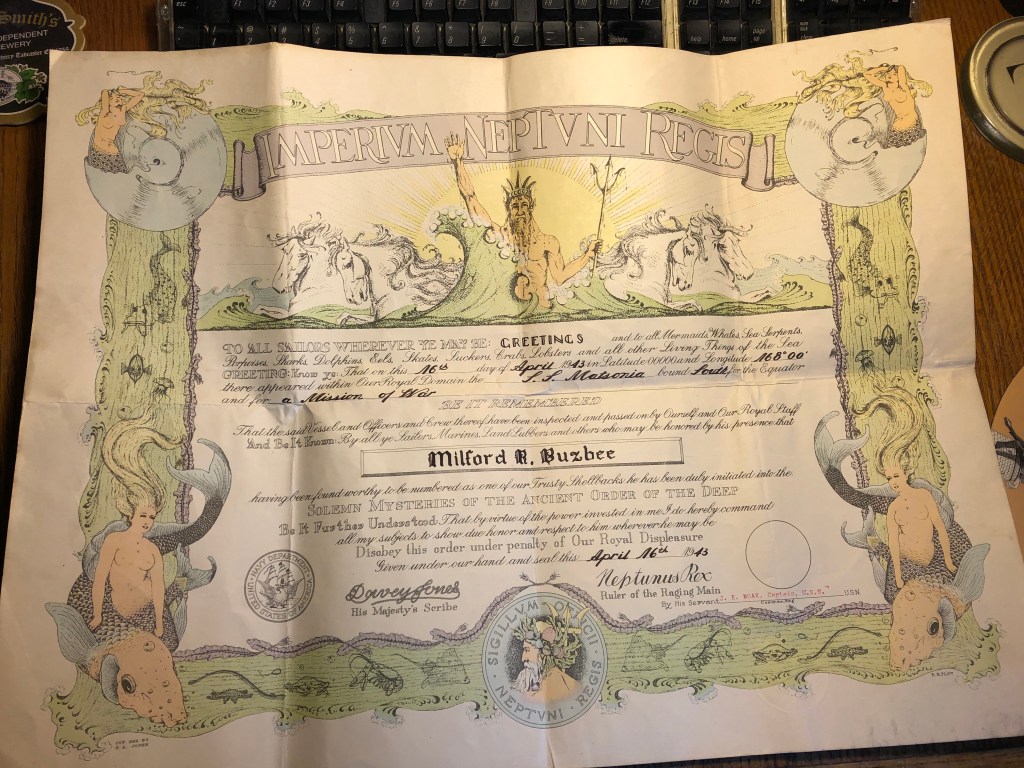

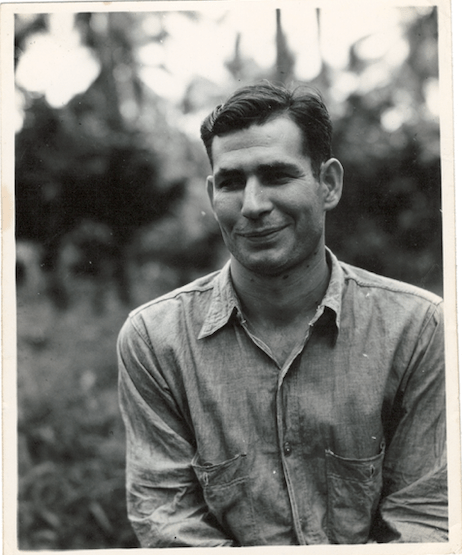

I had a deep and loving bond with my father, all through my childhood, and that loss shaped my entire life—may very well have contributed to my becoming a writer a few years later. I wanted to honor my father’s life, which was rather vagabond. His family left Oklahoma just as the Dust Bowl was creating havoc, they went to Los Angeles, where he and his brother were left in an orphanage for a year, then the family moved up to Oregon, his father walked out on the family, then they moved to Modesto, in California, where they built a house from old orange crates, then he roamed the West for a year, alone, at 14, working eventually on a horse ranch, then he lied about his age and joined the Army at 15, then after Pearl Harbor joined the Navy, where he became a deep sea diver and was constantly at sea. Always looking, it seems, for a home he never had, which he then found, after he retired, in San Jose, with my sister and brother and myself. It wasn’t a hero’s life, but, I’ve always felt, an heroic one.

I know Diver is based on your own childhood, but you chose to write it as a novel. What made you decide to tell your story this way? Does it give you more freedom?

Much of the book is based on my stories about his life that my father told me, and so I had to bring my imagination to those scenes, in order to fill them out. And even the parts of the book based on my own memories, well, those memories are also 55 years old now. There is a solid truth at the heart of each of these shards, but I’ve used my imagination to enliven them, to give them body on the page. The freedom of the fiction writer, however, allowed me to use those techniques to animate the past, while, I hope, never veering far from it. Art is the lie that reveals the truth, yes?

The past feels so vivid, so present on the pages, as if it’s alive in the here and now. I can hear it, smell it, taste it, and see it. Did you write everything from memory, or did you also need to research and dig deeper?

I did some research, especially surrounding those parts of my father’s life before I came along—the names of ships, facts about diving, various geographies, what was on TV on a given night, etc. But mostly I dove—excuse the pun—into my memory. I’ve discovered over the years that the more I dive into memory, the more my memory yields. As if it were a muscle that simply needed training. The more I stay in memory, the more it reveals to me. With this book, there was so much pleasure in staying in those memories, living in that time and space again—especially my childhood in the 1960s. It all came to life once more. Ah, the joy of that, being with those people in those places.

Were there any memories that resurfaced unexpectedly, things you thought you’d forgotten?

Nothing repressed came up, if that’s what you mean. I have always been someone who spends a lot of time in my own memories, trying to make sure they don’t leave forever—and surely this was the case with my father’s life. So, no, no surfacing memory surprised me; the surprises came as I wrote into these memories and discovered all the details and textures, shades of light and weather that I found there—and remembered again!

While reading, I felt a mix of emotions: happiness, anger, sadness, and so much laughter. What kind of emotions did you experience while writing the book?

I very much tried to be true to the stories and memories, the real life of our lives, and so there are all those emotions. I didn’t want to allow sentiment to infect these lives. And so, like life, there’s a whole range of emotions. But for me, it was, as I’ve already said, great pleasure in the writing. Oh, there were times when I did get emotional, in many ways, but always underneath that was the pleasure of memory.

Your dad was a diver, and he knew Jacques-Yves Cousteau. You capture so deeply the significance of the ocean and diving in his life. What does the ocean mean to you personally?

I spent the first four years of my life in Key West, Florida, which is where my father, still in the Navy, worked with Cousteau on Scuba technology. Our backyard in Navy housing was the ocean, nothing but ocean. And we were always in the water—my brother and father used to catch dinner, off our backyard. After he retired, we moved to San Jose, 30 miles from the coast, and we were always there, swimming and body surfing, and there was an endless parade of pools in our life. (Funny, my mother, oddly, never learned to swim.)

I once lived in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, for six months, thousands of miles from the ocean. I hated it. Even in San Jose, 30 miles from the coast, I could still smell the ocean in the fog and overcast. And now I live in San Francisco, three miles from the ocean, and the fog here, so common and so thick, well, I can always smell the ocean. The ocean is life, isn’t it, so why move away from it? And of course, nothing cures the soul as an hour staring across it, wondering at its breadth and depth. I’m a water baby.

Diving is also a strong metaphor. We dive into the book, we dive into the past. Reading is an immersive experience.

Yes, isn’t that what reading is, leaping across the threshold of your “real” life into a world that’s as vast and filled with life as the ocean. You are a stranger there, yet you feel so at home. And in the best books, you can take off your diving gear and swim unaided, free in those enchanting depths.

With Diver, you took complete control. You wrote it, designed it, published it, and even toured bookshops to sell it. Is this the future of publishing?

I took on this project, publishing my own book, because of my background in the book business. I was a bookseller for 10 years, and worked in publishing for 10 years, and even after I left, I continued to write about books and bookstores, and to remain a part of the very vibrant Northern California book community. For a book this personal, well, it felt like the right time. Just yesterday—this is in February—I received a picture of the book on a feature table in a bookstore I’ve never visited. That was thrilling, to know that I’d designed it and produced it and marketed and sold it, and there it was! One step away from finding a reader.

I do think that more and more writers will choose this route, though to what extent I can’t say. I’d published 7 books with mainstream publishers before this, I’ve been very luck that way. But there’s something about the control over the book that was so satisfying. ISelf-publishing is no longer about writers not being able to find a publisher; rather, it’s about creating a publishing experience that’s more fruitful in many ways.

What’s the hardest part of being a writer, and what makes it all worthwhile?

The hardest part? Understanding that you must make time, must will yourself to the desk. It sounds very uncreative to say, I know, but, really, it’s up to the writer to staple their butts to the chair. That’s how it gets done. And it’s there, in that discipline, that one’s creativity can come to its full power.

I love writing, that’s what makes it worthwhile. The reading, the note-taking, staring out the window, the composing, the revisions, all of it. The pleasure of creation. And whatever you’re creating—music or art or cooking or… The pleasure of creation. For me, it’s all about that, the creation. Everything else, publications or awards or money, those are nice but not necessary at all. To create something, and to have a reader—it’s only one reader at a time—bring that creation to life in their readerly minds? Wow.

What do books do better than anything else?

Connect you to the world. Yes, we do read for escape, and that’s wonderful, but mostly I think, we read to feel more alive in the world, to see the world more clearly and urgently. The best books make me want to get out of my chair and into the world.

Tell me more about Sparky. On the page she felt like an imagined dog!

Best dog ever. Sparky was four when I was born, and she immediately—a border collie/collie mix—made me her charge. Never far from my side—a fact my older brother never forgave me. She was a dog of another time—as am I, I suppose. She had her own life, wandered where she would, yet always returned. She was not trained nor restrained, and didn’t live a life of constant treats-for-good-behavior. She was a dog, not a pet. I still miss her.

I have a feeling you’re working on something new. Is that true?

Writers are always working on something new. Which must irritate their friends, who have to hear all about it. I’m deep into a notebook for a novel I’m calling Boy, for now. This boy was taken, at the age of nine, from his home on Crete to the beaches of Troy, where he worked in the Greek kitchens. But now, at 15, he’s just about to be sent into battle. But then again, there are a few other books pacing around that one; I never know which one will make it to the page.

Do you still want to be an astronaut?

I still feel crushed that when I was a child, I learned I would not be an astronaut because of my bad eyesight—back then astronauts had to have 20/20 vision to qualify. But now, given the chance, I think I’d much rather sail in a submersible vessel to the deepest parts of the ocean. Think of it! That’s where the real exploration is happening.

Thank you, Lewis, for the interview.

Leave a reply to Letter from February – Sea Library Cancel reply