“He would have to talk to the sea about it.”

Tove Jansson “Moominpappa at Sea”

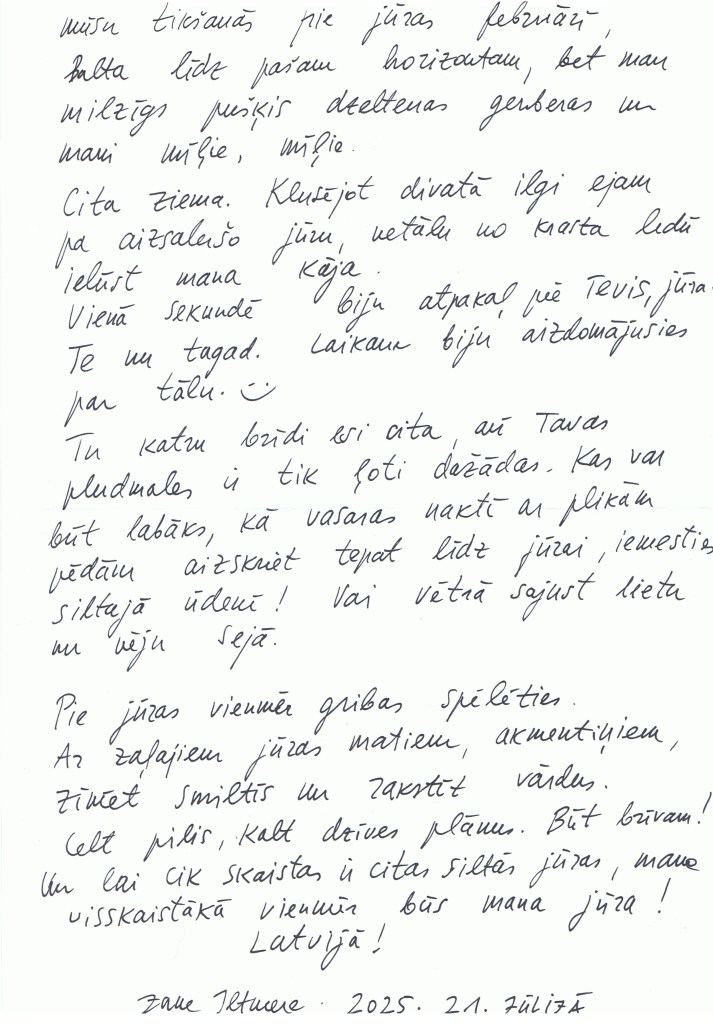

The sea arrives in envelopes, ink, and memories. Over the past months, seven letters have reached the Sea Library from different shores: the Atlantic in Cornwall, the Baltic Sea along Rīga, Jūrmala, Saulkrasti and Jūrkalne, the Pacific fogs of San Francisco, and even the frozen horizon of winter beaches. Each letter carries a piece of its writer’s coastline, and together they form a map of how we meet the sea – not just with our feet in the sand or salt on our skin, but in the rituals, stories, and silences we bring to it. These letters reveal not only the seas themselves but the ways we live beside them: walking their edges, naming their colors, and sometimes holding back at the shoreline or, completely opposite, diving right in.

This first stack of letters carries something personal. Most of these seven writers are among the people closest to me: my mother Zane, my sister Katrīna, my best friend Marta and her mother Ilga, and my companion in writing and exchanging letters about everything – Lewis. It’s moving to see how each of them, in their own voice, turns to the sea not just as a subject, but as something alive in their lives. And thank you to Neil for being the first to believe in this initiative and writing the very first letter to the sea. And to Ieva for being the first from my land to send hers.

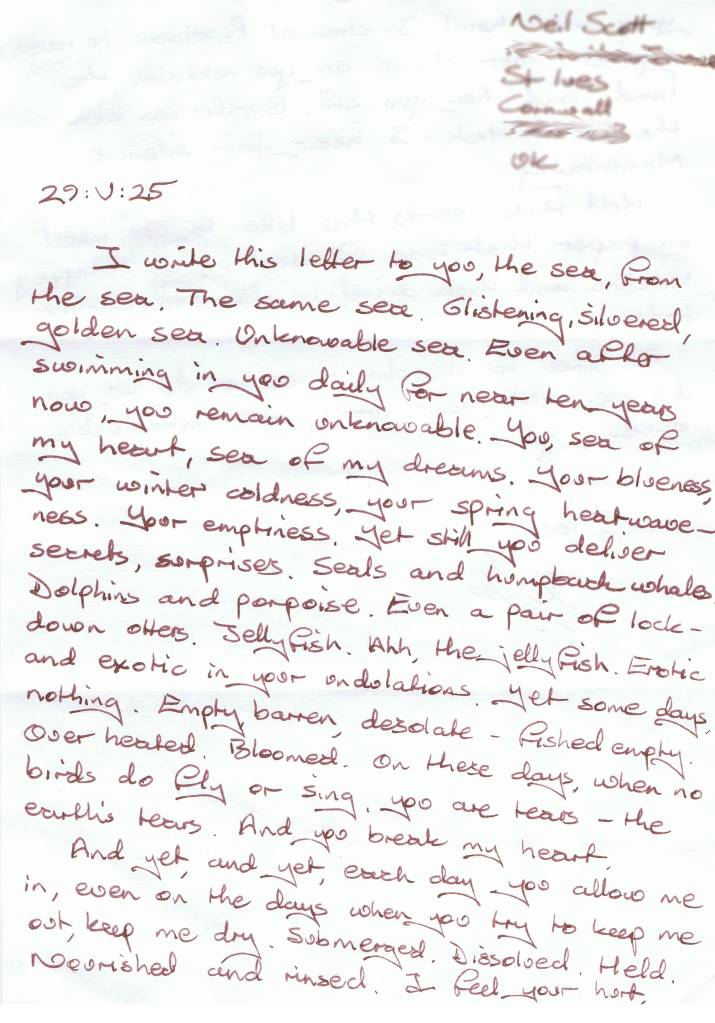

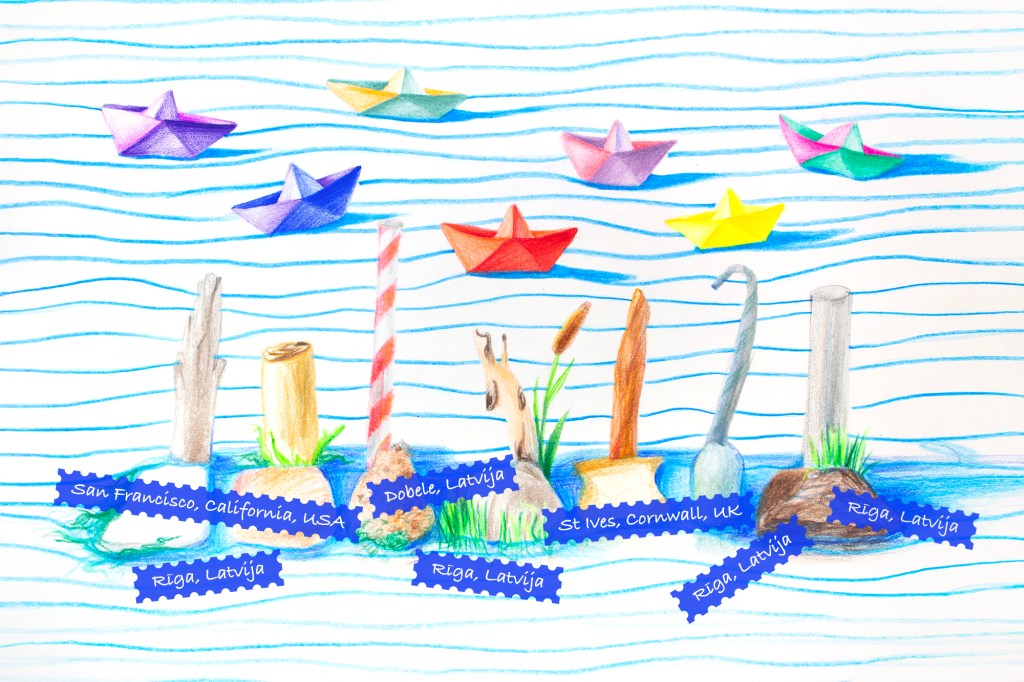

Neil Scott – Rituals of the Atlantic

Written on white paper with brown ink, Neil’s letter comes from St Ives, where the Atlantic is less a backdrop than a companion – a mysterious one, still unknowable even after a decade of swimming in it. He writes to the sea from the sea, describing a relationship of daily closeness through all four seasons: swimming in its tides, listening to its voice and its silence, watching seals, dolphins, otters, jellyfish, and even whales move through its depths. His tone is reverent and elemental, as if his words were part of the same tide-pulled rhythm. He invokes sea mythology by channeling Poseidon, and ecology by acknowledging the many bad things that have happened to the sea.

The Atlantic in Neil’s letter has no boundaries between human and ocean; it is kinship. He even lets the letter itself touch the sea – paper floated and sun-dried, a ritual that binds text to its subject. “You, sea of my heart, sea of my dreams.”

The envelope is white, with a green King Charles stamp.

Neil has included a gift: a tiny painting on paper.

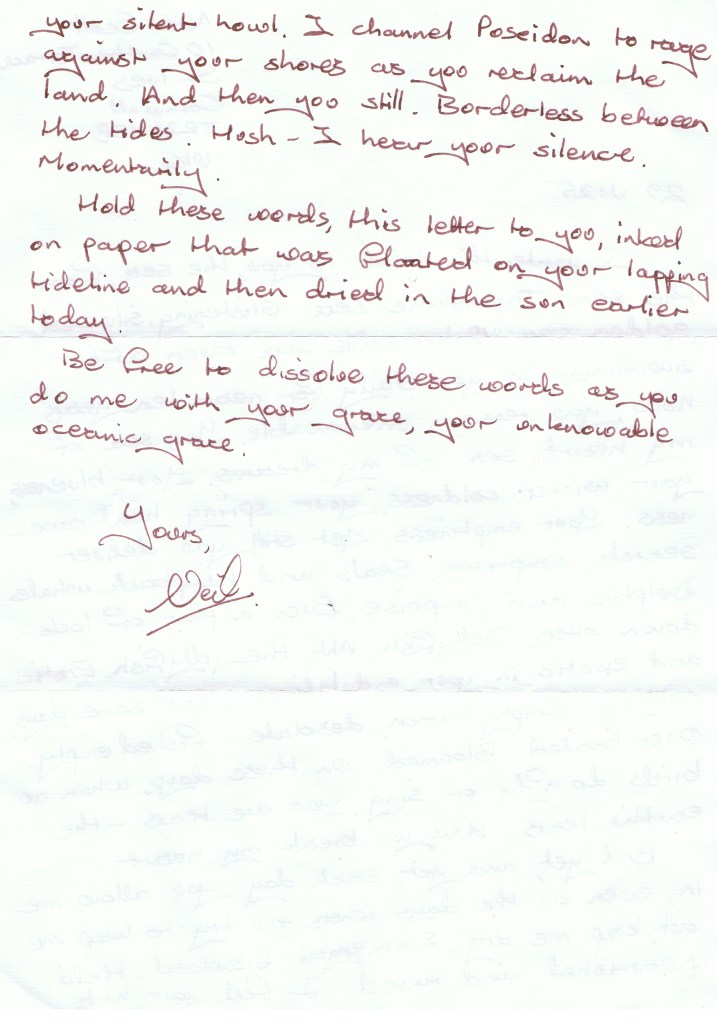

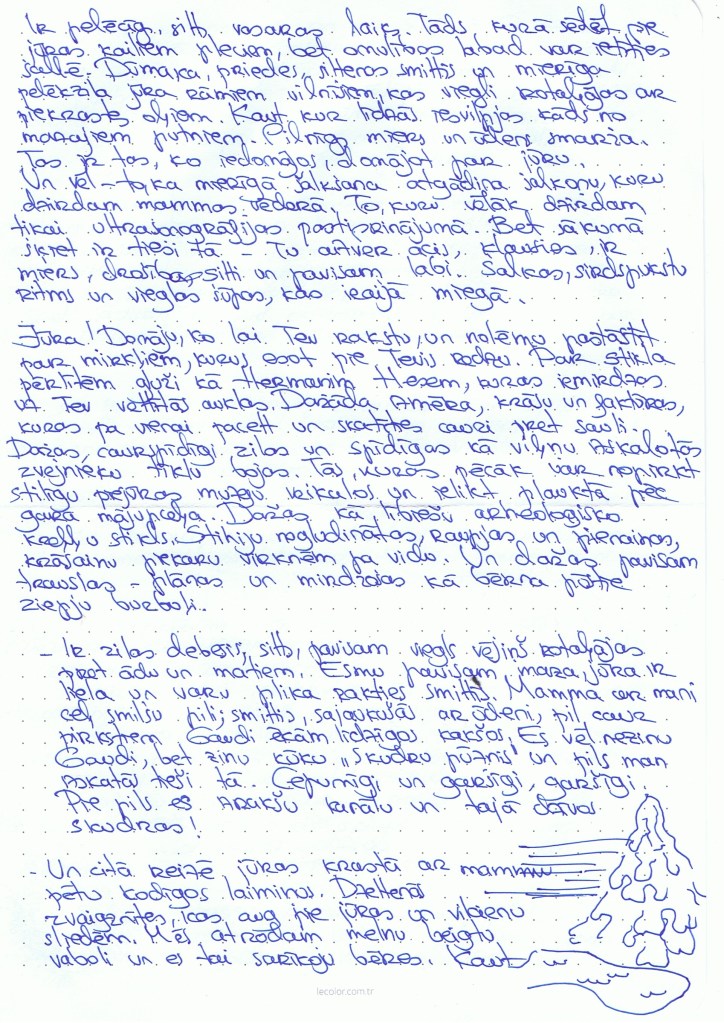

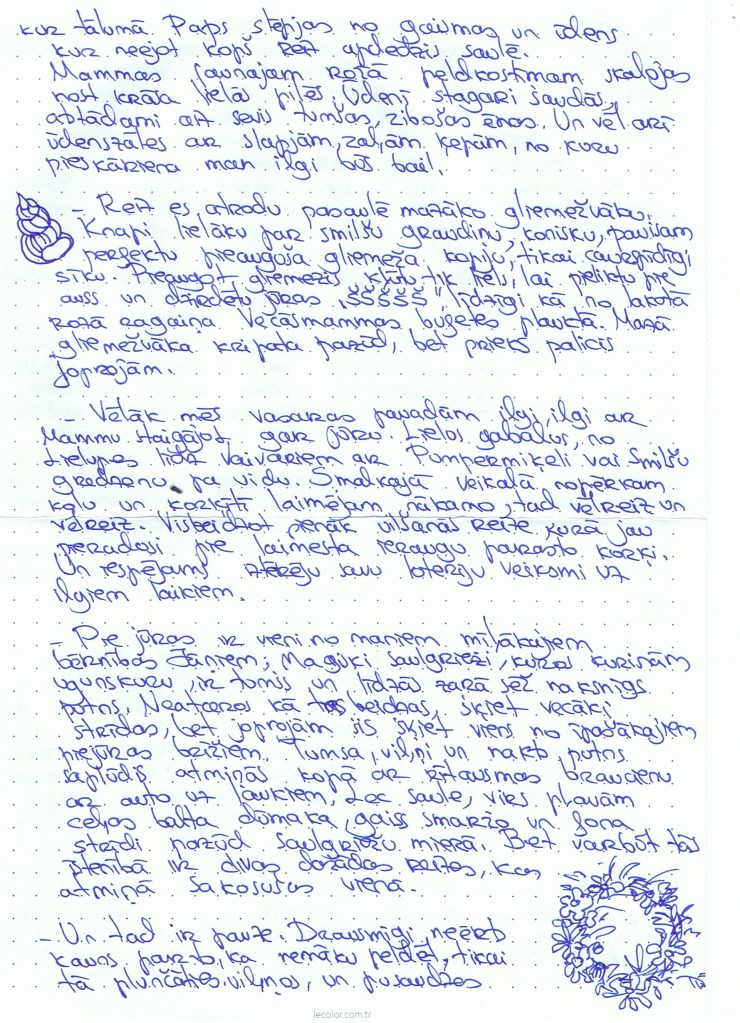

Ieva Ēkena – a string of memory pearls

For Ieva, the Baltic Sea is the language of memory. Her letter, written on white dotted paper in blue ink, begins with an exclamation – “Sea!” – as if addressing an old friend. She writes about the sea from the days of her childhood, when time spent on the beach was shared with her father and mother; about the turbulent teenage years, when it was hard to feel comfortable in one’s own body; and about the liberating years of growing up, ending the letter with her own little child held close to her heart, right there by the sea. Ieva’s sea is familial. Midsummer night with her parents. Long walks with her mother. The wrong friends and breakups, and true walks with the right person. The exotic seashell kept in her grandmother’s buffet. The sea is present in all of it.

Ieva’s sea is full of sounds and moods, colors and the presence of nature: waves we can hear already in our mother’s womb, seabirds at night, darting sandpipers, seaweeds, goldmoss stonecrop – the little yellow star-like flowers – on the dunes, and the world’s tiniest seashell. Ieva’s sea is also culture and history: she mentions the glass floats of fishermen’s nets, the ancient Livonian glass jewelry, and compares sandcastles to Gaudi’s architecture.

Literature also easily takes root along her shore. Spinning memories of the sea, Ieva evokes the glass bead metaphor from Hermann Hesse, references Tove Jansson’s Moomins and The Summer Book, Astrid Lindgren’s Ronja and The Seacrow Island, as if the Baltic Sea itself – uniting the coasts of Latvia and Scandinavia – carries the same quiet, playfully melancholic mood. In Ieva’s letter, the sea is not merely a landscape – it is a story, and the child in that story never fully grows up.

A brown kraft paper envelope bears a Latvian national costumes stamp and a drawing of a paper boat.

Ieva has also illustrated her letter with delicate drawings scattered throughout – a shell, a dripping sandcastle, a solstice wreath and Moomin.

Ilga Ķipsne – The Horizon in Song

Ilga writes on white paper with a blue ink from inland Dobele, but her Baltic is a remembered sea, although she visits it often. She addresses it simply: “Jūra,” in Latvian, as if naming it was enough to summon it. Her tone is meditative, almost elegiac. She does not swim or walk its shore in the letter; instead, she holds it at a respectful distance, through memory and culture, compares ir to a wild stallion and speaks about courage. Suiti folk songs drift through her words – echoes of an older rhythm where the sea as a horizon passed from generation to generation.

Her letter reminds us that the sea can live in us even when we are far from it, carried in language and ancestral sound and that probably a meaning of the sea is encoded in these songs.

The dark blue envelope bears a stamp featuring Latvian national costumes.

Ilga has included a gift: a paper bookmark printed with a photo of a road through a forest and a poem in a local dialect about being anchored and being shaken by storms.

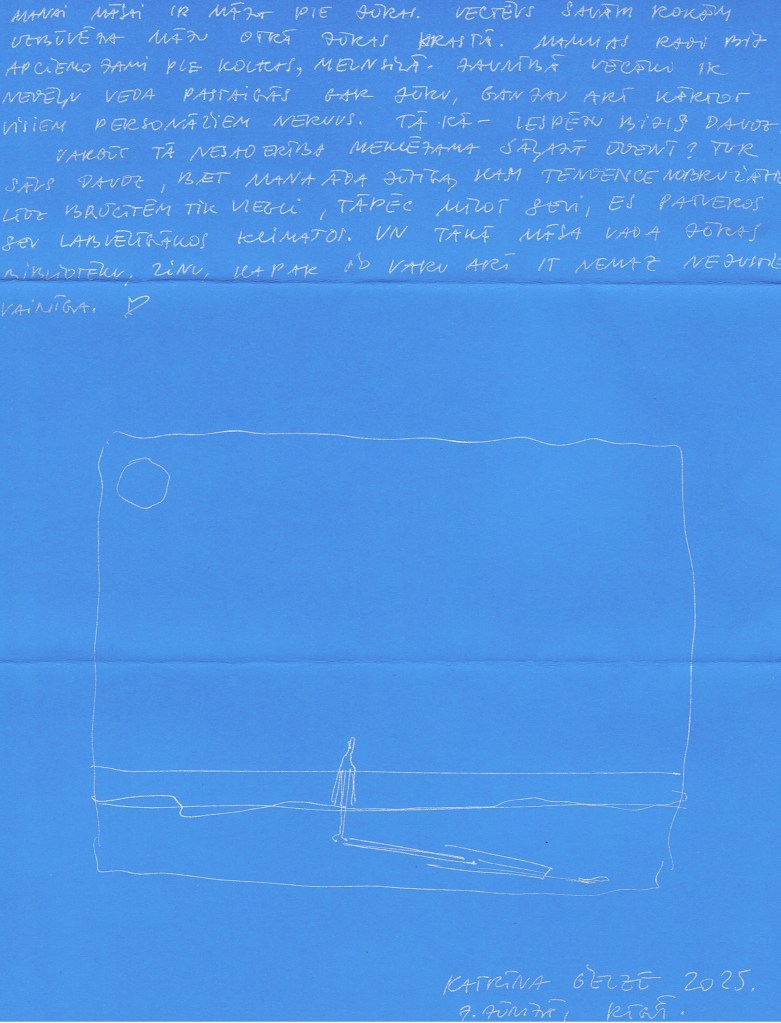

Katrīna Ģelze – Honest refusal

Katrīna’s letter, written on azure-blue paper in silver ink in Riga, is different. While others approach the sea with longing, joy, or ritual, she keeps it at a distance. Her tone is sharp and honest—she admits that she cannot stay by the sea for too long, feels vulnerable on the open beach under the vast sky, is afraid to swim in its cold waves, and her sensitive skin may not tolerate the salt; she openly expresses disappointment when, even in life’s most decisive moments – such as when her father awakens from a coma – she feels nothing exalted when by the sea.

For Katrīna, the sea is an edge, a boundary not to be crossed. She writes with pleasure only about Jūrkalne in her childhood, about its stones and winds, but her relationship with the Baltic Sea is still being worked out. And yet, this frankness is a form of intimacy. Her honesty transforms distance into another way of knowing the sea – a love defined by candid explanation, with all the cards laid on the table.

A white Milka chocolate envelope with purple motifs features Latvian national costumes stamp and a drawing of dripping water with blue drops underneath it.

At the end of her letter, Katrīna has included an illustration of a human figure on an empty coast, casting a long shadow.

She has also added two gifts: collectible Lego character cards featuring a sailor and a sea captain.

Marta Leimane – Sea as Threshold of Change

Marta’s letter meets the Baltic Sea in late November – sharp, cold, stripped of its summer gentleness. She walks through pine woods and empty dunes until she finds herself on the edge of dark waves, under a sky she describes as “pale like bone.” In that moment, the sea becomes a threshold – not a place of grief alone, but of transformation. She writes of stepping into the water and dissolving into its molecules, of being both lost and held. It’s a rare, raw encounter with the sea as witness and participant in deep inner change.

Her tone is cinematic and poetic, charged with honesty. Marta doesn’t dramatize; she surrenders. The act of entering the water becomes a wordless ritual, one that quietly restores something in her. The sea receives her not as someone in mourning, but as someone becoming. Her letter is a tide itself – moving from solitude to a kind of silent levitation, from the land of thought to the body’s language of salt and water. And like Neil, she lets the sea touch the letter itself – one page is dipped in saltwater, as if the Baltic had signed it too.

The envelope is white and secure, with a bubble wrap lining, as if carrying something fragile. It bears a stamp depicting Latvian national costumes, with a drawn line underneath that makes it look as if the stamp is melting into water.

Marta has included many black-and-white art photographs, probably from the notebook whose pages were used to write her letter.

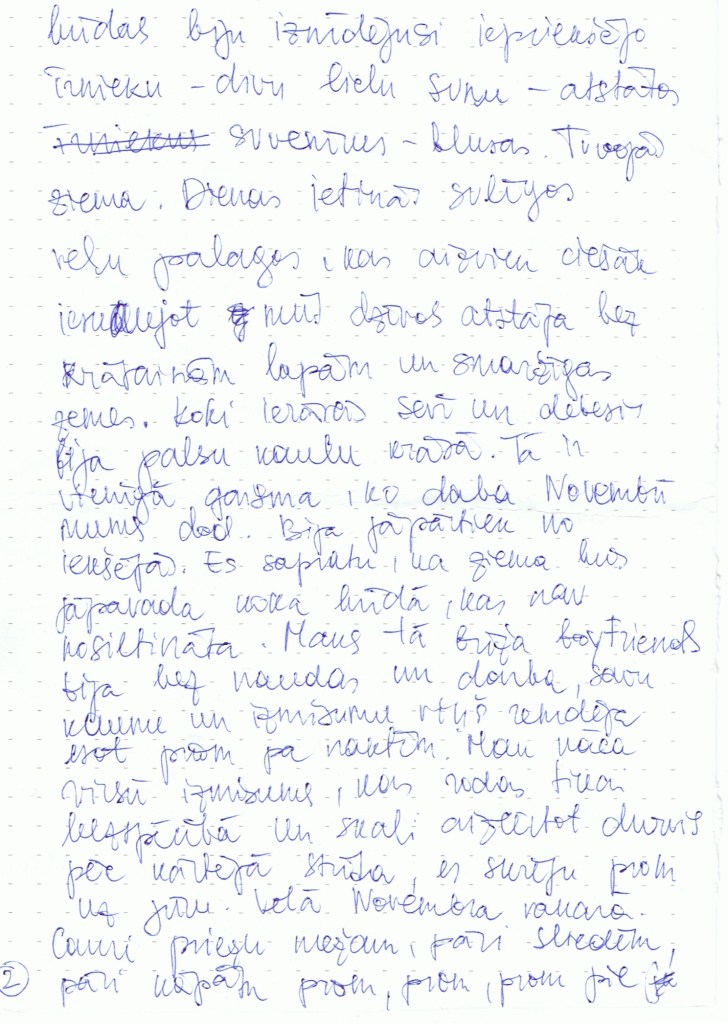

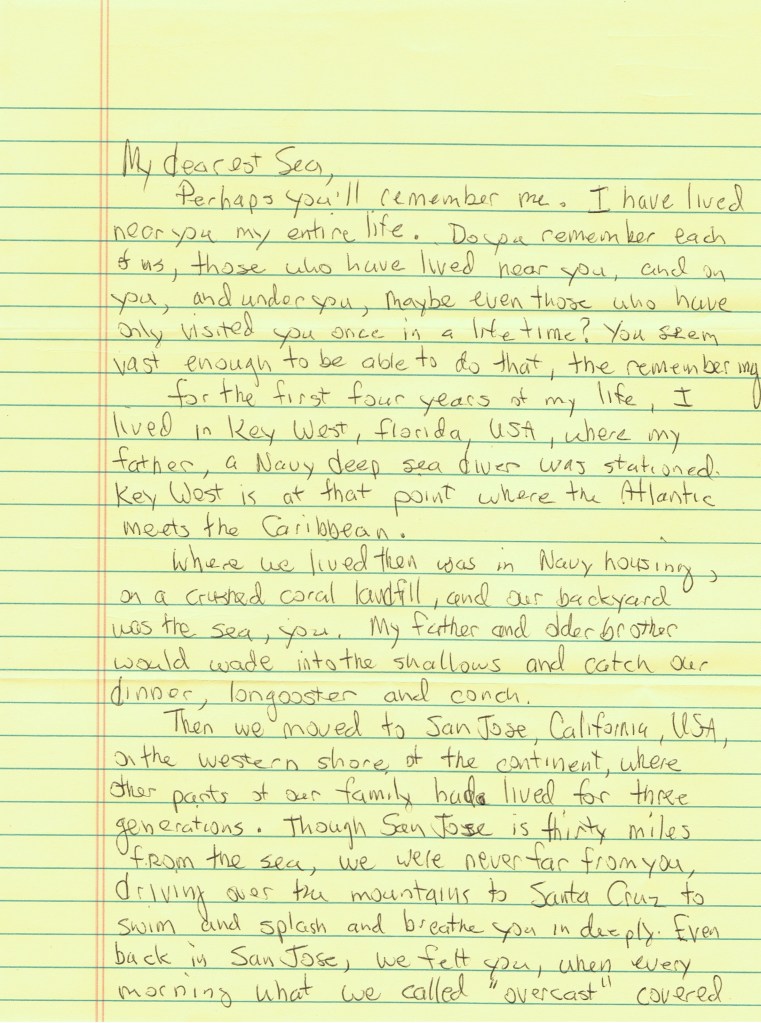

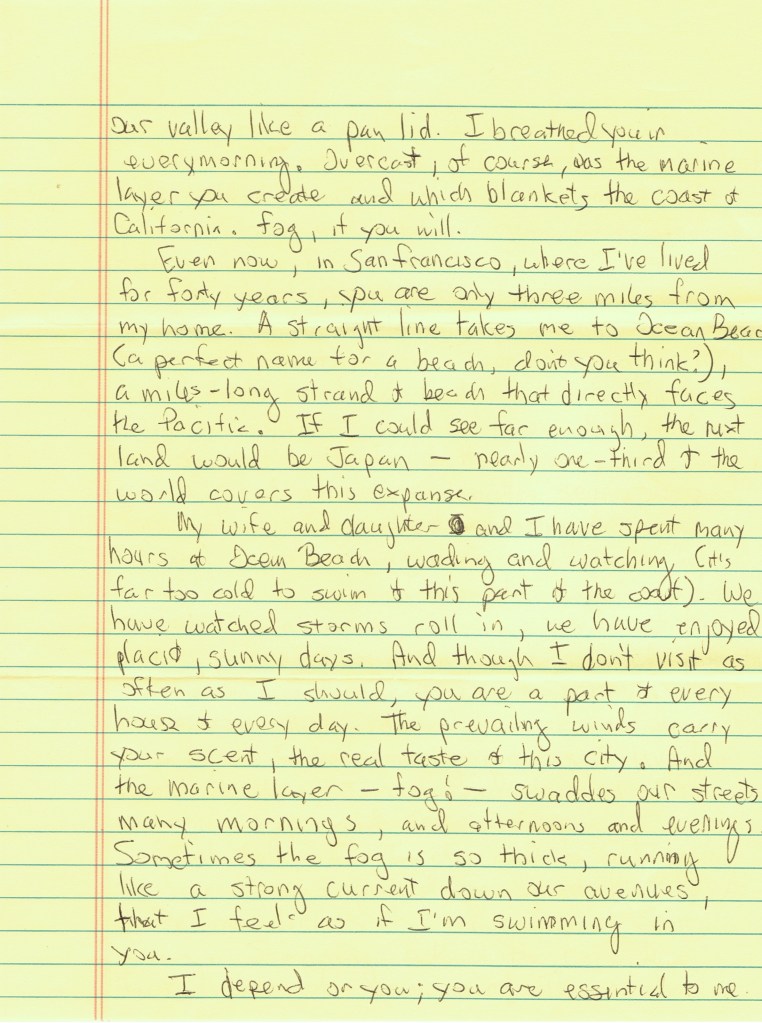

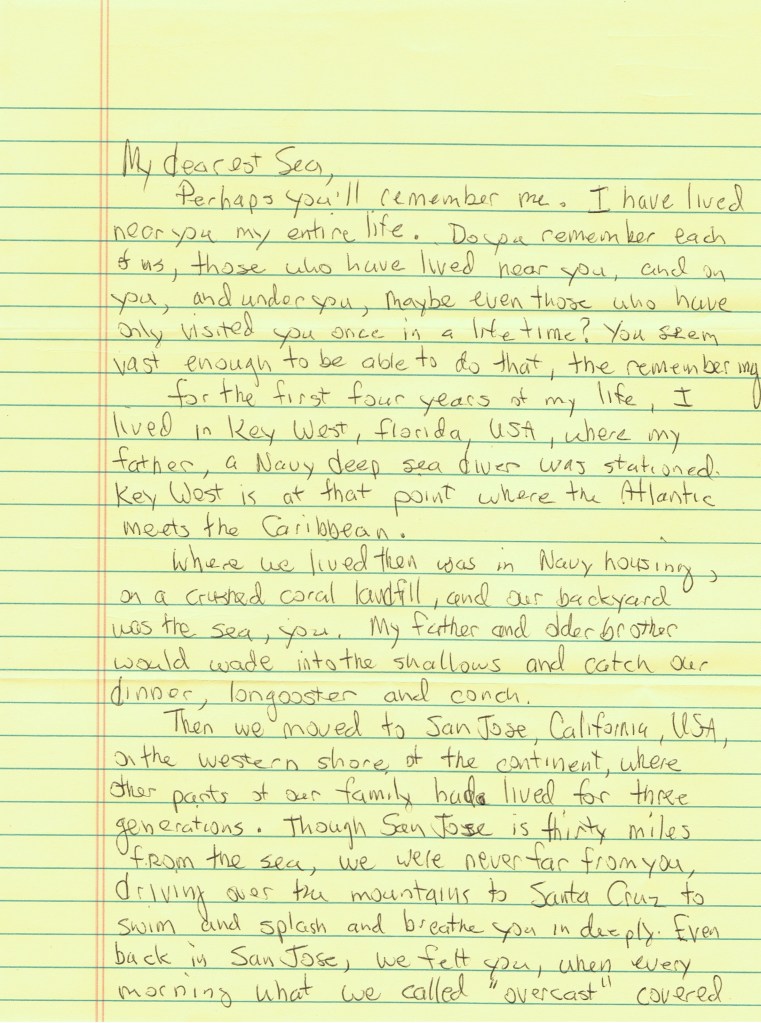

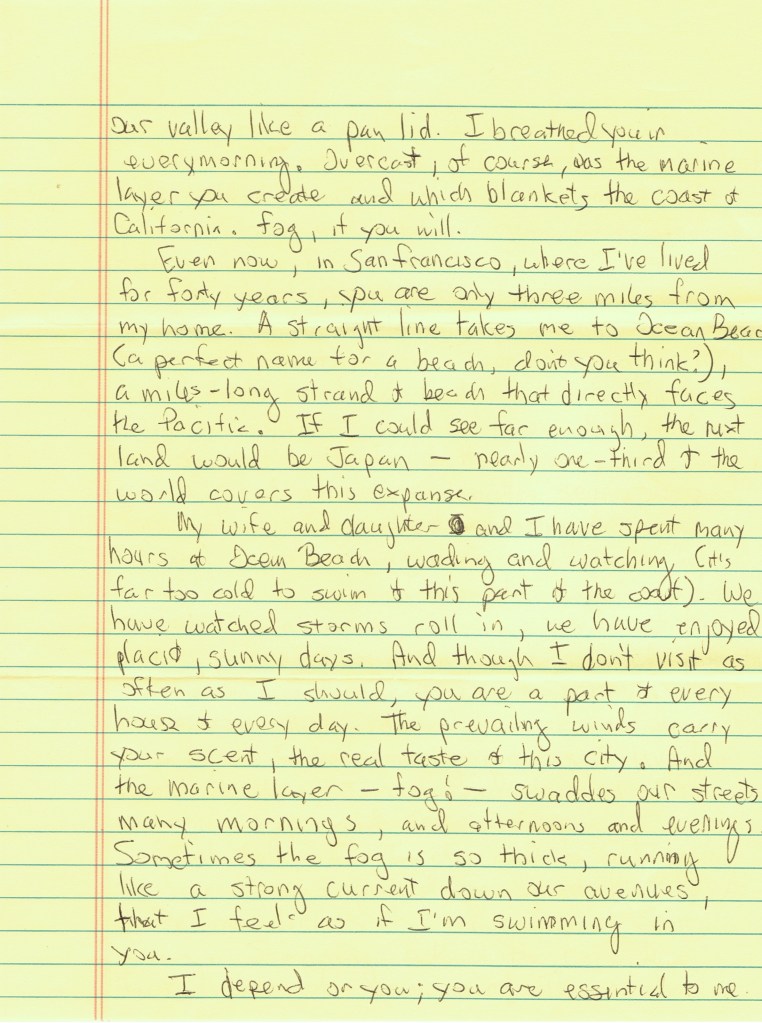

Lewis Buzbee – Fog, Memory, and Closeness

Lewis writes from California, where the sea is never just a backdrop—it’s in the wind, the fog, the streets themselves. “My dearest Sea,” he begins, and from there, we feel his intimacy with the ocean deepen line by line. He doesn’t write only about his own memories; he wonders if the sea has memories too. Does the sea remember us? “You seem vast enough to be able to do that, the remembering.”

He recalls the waters of his childhood – wading off Key West, where the Atlantic meets the Caribbean, his father and brother catching seafood for dinner. Now his coast is the Pacific in San Francisco, and he walks to Ocean Beach as often as he can with his wife and daughter. The ocean permeates his life, shaping his breath, his thoughts, his sense of home.

There is no distance in his letter – only presence. Even when inland, he writes of being haunted by the sea’s absence, as if too much time away from its edge dissolves his grounding. Fog becomes a metaphor for water itself, rolling into city streets like a reminder: the sea is always near. The sea, for Lewis, is not far away – it lives with him, quietly and constantly.

The envelope is white and classic.

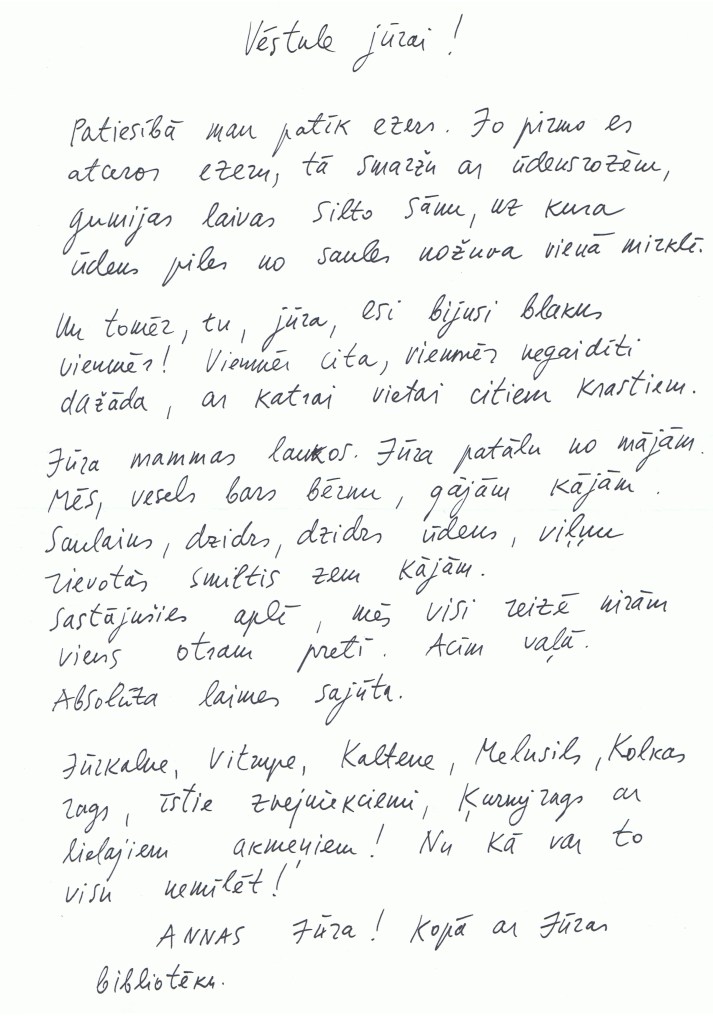

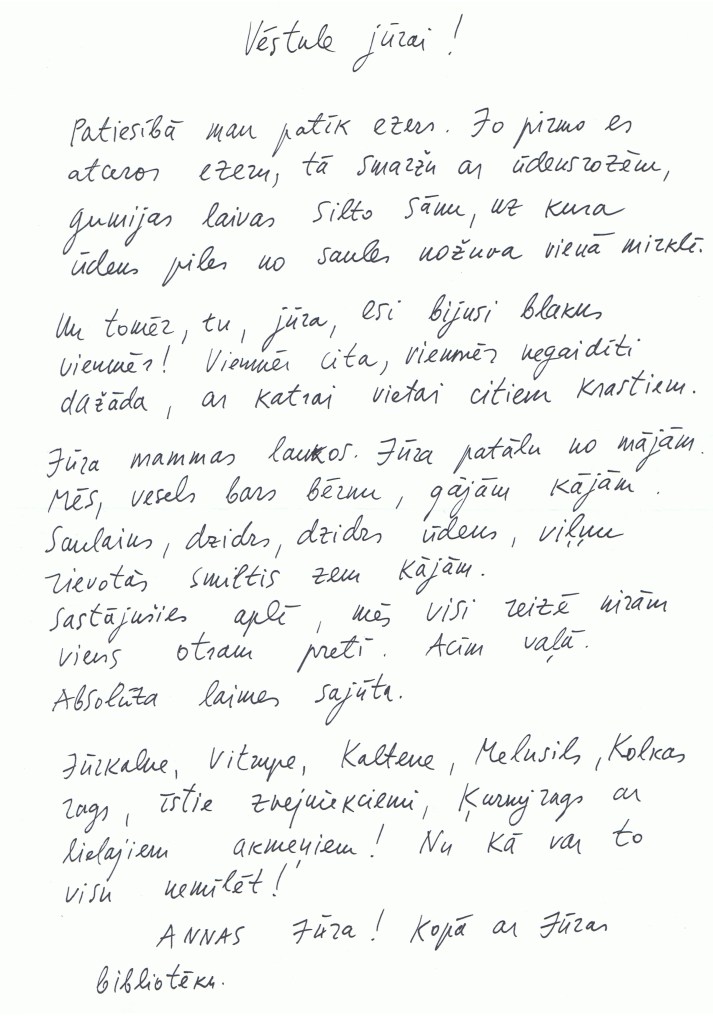

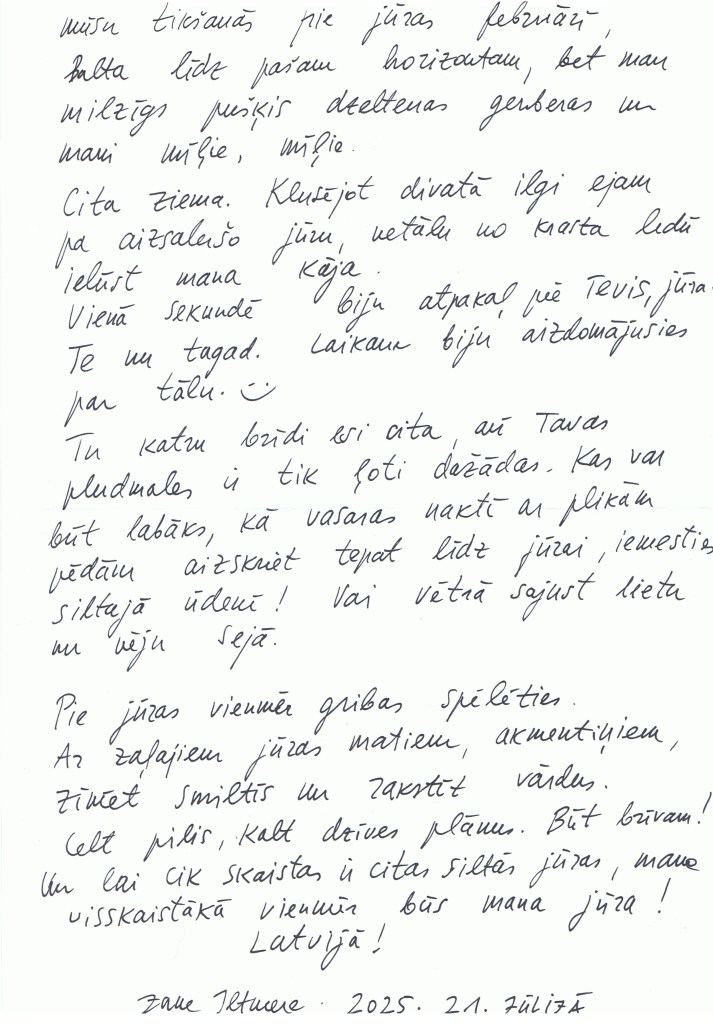

7. Zane Iltnere – The Sea as a Playground of Freedom

Zane’s letter begins with memories of a lake scented with water lilies and the warm rubber of a sun-heated boat. But it is the Baltic Sea that brings her a sense of freedom. She recalls her childhood, diving wide-eyed into the clear waves alongside other children. They played underwater as if in slow motion – bodies light and fluid – and the sea gave them not only space, but permission: to play, to explore, to belong.

In her words, there is joy and certainty that the sea has always meant freedom and play. Even in winter, when it freezes white all the way to the horizon, she walks across it with others, and when a foot breaks through the thin crust of ice, the moment pulls her fully into the here and now.

Zane’s letter is full of movement and affection: a long, playful dance with and along the sea, embracing the many different beaches of Latvia – Jūrkalne, Vitrupe, Kolka. She writes not with nostalgia, but with gratitude – for a sea that is never the same, yet always takes her back, and can be compared to no warm southern sea.

The envelope is white and classic and bears a stamp featuring Latvian national costumes.

Zane has included a gift: a photo of sunlit sand ripples.

***

I will start publishing the next seven letters next Wednesday. Have you written yours? I know you have a story to tell the sea. I’ll give you the post box address: beachbooksblog@gmail.com.

Anna

Sea Librarian

“Viņam jāaprunājas par to ar jūru.”

Tūve Jānsone “Tētis un jūra”

Jūra atnāk aploksnēs, tintē un atmiņās. Pēdējo mēnešu laikā Jūras bibliotēku sasniegušas septiņas vēstules no dažādiem krastiem: Atlantijas okeāna Kornvolā, Baltijas jūras gar Rīgu, Jūrmalu, Saulkrastiem un Jūrkalni, Klusā okeāna miglā tītajiem krastiem Sanfrancisko un pat no ziemā aizsalušas jūras horizonta. Katra vēstule nes sevī daļu no tās autora krasta, un kopā tās veido karti, kurā redzams, kā mēs satiekamies ar jūru – ne tikai ar pēdām smiltīs vai sāli uz ādas, bet arī ar rituāliem, stāstiem un klusumu, ko tai atnesam. Šīs vēstules atklāj ne tikai dažādās jūras, bet arī to, kā mēs dzīvojam tām līdzās: ejot gar krastu, saucot ūdens mainīgās krāsas un reizēm apstājoties pie pašas malas vai, tieši otrādi, metoties iekšā.

Šī pati pirmā vēstuļu bunte glabā vēl ko pavisam personīgu. Lielākā daļa šo septiņu rakstītāju ir mani vistuvākie cilvēki: mana mamma Zane, māsa Katrīna, labākā draudzene Marta un viņas mamma Ilga, kā arī mans literārās rakstīšanas un ikdienas vēstuļu draugs Lewis. Ir aizkustinoši redzēt, kā katrs savā balsī vēršas pie jūras ne tikai kā pie tēmas, bet kā pie dzīva klātbūtnes spēka savā dzīvē. Un paldies Neil, kurš pirmais noticēja šai iecerei un uzrakstīja pašu pirmo vēstuli jūrai, un Ievai – par to, ka viņa bija pirmā no manas zemes, kas nosūtīja savu.

Neil Scott – Atlantijas rituāli

Uz balta papīra rakstīta ar brūnu tinti, Neil vēstule nāk no Sentīvzas, kur Atlantijas okeāns ir ne tik daudz fons kā sabiedrotais — noslēpumainā, joprojām neizzināmā jūra pat pēc desmit gadiem, ko viņš tajā peldējis. Viņš raksta jūrai no jūras, aprakstot ikdienas tuvību caur visām četrām sezonām: peldēšanu tās paisumos, klausīšanos tās balsī un klusumā, vērojot jūras lauvas, delfīnus, ūdrus, medūzas un pat vaļus. Viņa tonis ir cieņpilns un stihisks, it kā vārdi būtu daļa no tā paša paisumu un bēgumu ritma. Viņš atsaucas uz jūras mitoloģiju, iemiesojot Poseidonu, un uz ekoloģiju, atzīstot daudzās likstas, ko mēs tai esam uzkrāvuši.

Neil vēstulē Atlantijas okeānam nav robežu starp cilvēku un okeānu; tā ir radniecība. Viņš pat ļauj pašai vēstulei pieskarties jūrai — papīrs tiek iemērkts un pēc tam žāvēts saulē, rituāls, kas sasaista tekstu ar tematu. “Tu, mana sirds jūra, manu sapņu jūra.”

Aploksne ir balta ar zaļu karaļa Čārlza pastmarku.

Neil sūta līdzi mazu glezniņu uz papīra.

Ieva Ēkena – Atmiņu pērļu virtene

Ievai Baltijas jūra ir atmiņu valoda. Viņas vēstule, uz balta punktota papīra ar zilu tinti, sākas ar izsaucienu – “Jūra!” – it kā uzrunājot senu draugu. Viņa raksta par jūru no bērna dienām, kur pludmalē pavadīts laiks ar tēti un mammu, par spurainajiem pusaudžu gadiem, kur ir grūti labi justies savā ķermenī, līdz atbrīvojošiem pieaugšanas gadiem, noslēdzot vēstuli ar jau savu bērniņu pie sirds un turpat pie jūras. Ievas jūra ir ģimeniska. Jāņu nakts ar vecākiem. Garas pastaigas ar mammu. Nepareizie draugi un šķiršanās, un patiesas pastaigas ar īsto cilvēku. Vecāsmammas bufetē glabātais eksotiskais gliemežvāks. Jūra tam visam ir līdzās. Ievas jūra ir pilna skaņu un noskaņu, krāsu un dabas klātbūtnes: viļņi, kurus dzirdam jau mammas dzemdē, jūras putni naktī, šaudīgie stagari, ūdenszāles, kodīgie laimiņi – dzeltenās zvaigznītes kāpās un pasaulē mazākais gliemežvāks. Ievas jūra ir arī kultūra un vēsture: viņa piemin zvejnieku tīklu stikla bojas, seno lībiešu stikla rotas un salīdzina smilšu pilis ar Gaudi arhitektūru.

Arī literatūra viegli ieaužas viņas krastā. Vērpjot jūras atmiņas, Ieva patapina stikla pērlīšu metaforu no Hermaņa Heses, piemin Tūves Jansones Muminus un “Vasaras grāmatu”, Astrīdas Lindgrēnes Ronju un “Sālsvārnas salas vasarniekus” it kā pati Baltijas jūra, kas vieno Latvijas un Skandināvijas krastus, nestu sevī to pašu kluso, rotaļīgi melanholisko noskaņu. Ievas vēstulē jūra nav tikai ainava – tā ir stāsts, un bērns šajā stāstā nekad līdz galam nepieaug.

Brūna kraftpapīra aploksne ar Latvijas tautastērpu pastmarku un papīra laiviņas zīmējumu.

Vēstulē ir arī Ievas smalkie zīmējumi – gliemežvāks, smilšu pilis, saulgriežu vainags, Mumins u.c.

Ilga Ķipsne – Apvārsnis dziesmā

Ilga raksta no iekšzemes – Dobeles – uz balta papīra ar zilu tinti, bet viņas Baltijas jūra ir atmiņu jūra, lai gan viņa to bieži apciemo arī tagad. Viņa uzrunā to vienkārši: “Jūra”, it kā pietiktu to nosaukt, lai tā būtu klāt. Tonis ir meditējošs, teju elēģisks. Vēstulē viņa nepeld un nestaigā gar krastu; tā vietā jūru tur cieņpilnā attālumā, caur atmiņu un kultūru, salīdzina to ar mežonīgu rumaku un runā par drosmi. Cauri vārdiem skan Suitu dziesmas – sena ritma atbalss, kur jūras apvārsnis pārmantots no paaudzes paaudzē.

Ilgas vēstule atgādina – jūra var dzīvot mūsos arī tad, ja atrodamies tālu no tās, iekodēta valodā un senās melodijās, un, iespējams, tieši šajās dziesmās glabājas jūras jēgas atslēga.

Tumši zila aploksne ar Latvijas tautastērpu pastmarku.

Ilgas dāvana – papīra grāmatzīme ar fotogrāfiju, kurā ceļš ved caur mežu, un ar dzejoli vietējā izloksnē par iesakņošanos un sabangošanos.

Katrīna Ģelze – Godīga pretestība

Katrīnas vēstule, rakstīta uz azūrzila papīra ar sudraba tinti Rīgā, ir citāda. Kamēr citi jūrai tuvojas ar ilgām, prieku vai rituālu, viņa to tur atstatus. Tonis ir skarbs un godīgs – viņa atzīst, ka pie jūras nespēj būt pārāk ilgi, liedaga klajumā zem debesīm jūtas neaizsargāta, jūras aukstajos viļņos baidās peldēt, jūtīgajai ādai, iespējams, nepatīk sāls, un viņa atklāti viļas, kad pat tādos izšķirošos dzīves mirkļos, kad tētis pamostas no komas, pie jūras nesajūt neko.

Katrīnai jūra ir mala, robeža, kuru nepārkāpt. Ar prieku raksta vien par par Jūrkalni bērnībā, par tās akmeņiem un vējiem, bet attiecības ar Baltijas jūru vēl šķetināmas. Un tomēr šī atklātība ir sava veida tuvība. Viņas godīgums pārvērš distanci par citu veidu, kā pazīt jūru – par mīlestību, kas definēta ar godīgu izskaidrošanos, kur visas kārtis ir galdā.

Balta “Milka” aploksne ar violetiem motīviem, Latvijas tautastērpu pastmarku un zīmētiem ūdens pilieniem zem tās.

Vēstules beigās – Katrīnas zīmējums: cilvēka figūra tukšā piekrastē, metot garu ēnu.

Viņas dāvanas – divas kolekcionējamas “Lego” tēlu kartītes: jūrnieks un kapteinis.

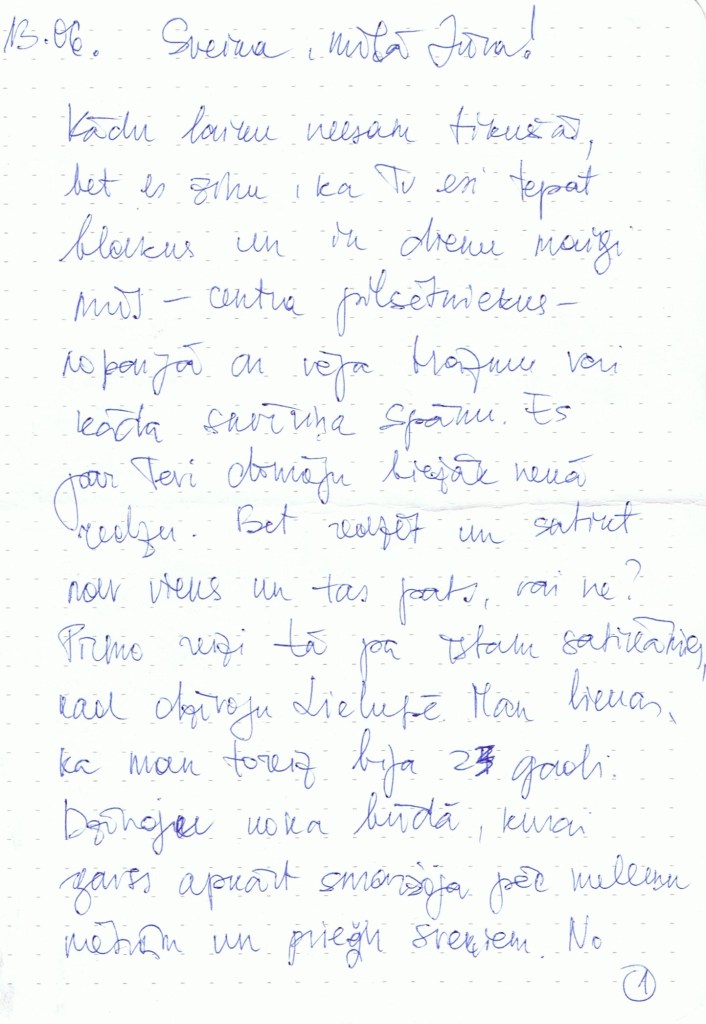

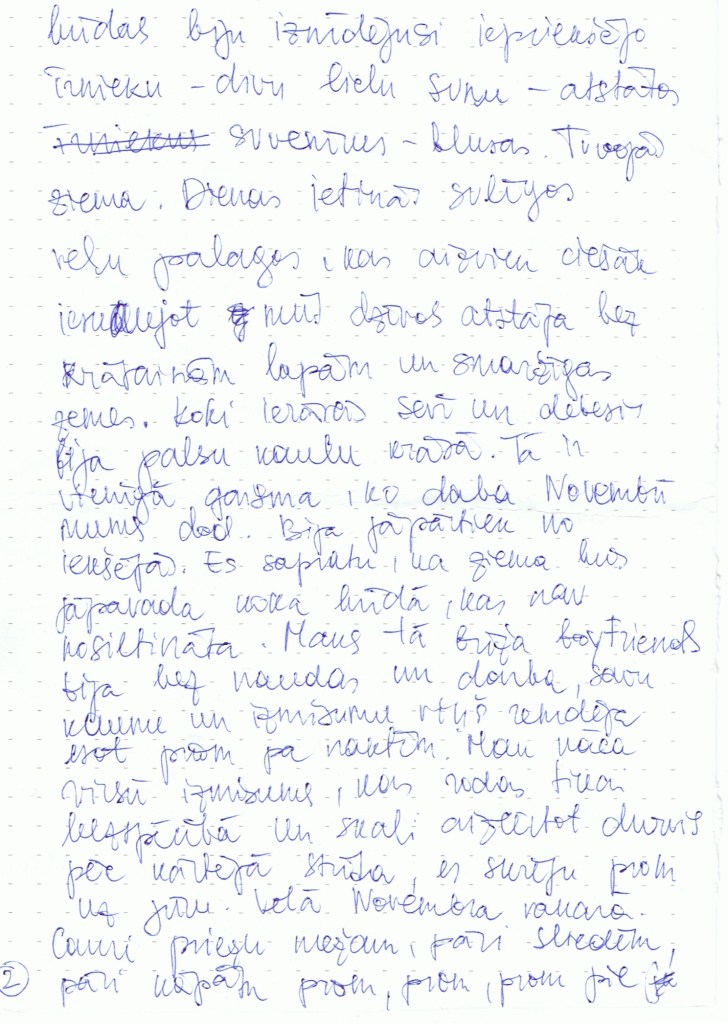

Marta Leimane – Jūra kā pārmaiņu slieksnis

Martas vēstule satiek Baltijas jūru vēlā novembrī – skarbu, aukstu, bez vasaras maiguma. Viņa iet cauri priežu mežam un tukšām kāpām, līdz nonāk pie tumšiem viļņiem. Tajā brīdī jūra kļūst par slieksni – ne tikai bēdu vietu, bet pārvērtību telpu. Marta stāsta par ieiešanu ūdenī un izšķīšanu tā molekulās, par būšanu reizē pazaudētai un atrastai. Tā ir reta, patiesa sastapšanās ar jūru kā liecinieci un līdzdalībnieci dziļās iekšējās pārmaiņās.

Martas tonis ir kinematogrāfisks un poētisks, pilns atklātības. Viņa nedramatizē, bet atdodas atmiņām. Ieešana ūdenī kļūst par klusu, bezvārdu rituālu, kas kaut ko viņā uzauž no jauna. Jūra viņu pieņem nevis kā nelaimes čupiņu, bet kā cilvēku, kurš pārtop. Vēstule pati ir kā ūdens kustība – no vientulības līdz levitēšanai jaunā dzīvē, no zemes, uz kuras domājam domas, līdz ķermeņa plūstoši intuitīvajai gudrībai. Un tāpat kā Neil, arī Marta ļauj jūrai pieskarties vēstulei – viena lapa ir iemērkta jūras ūdenī, it kā Baltijas jūra būtu pati to parakstījusi.

Aploksne ir balta un iztapsēta ar burbuļplēvi it kā tiktu sūtīts kas trausls. Tā nes Latvijas tautastērpu pastmarku, zem kuras ievilkta līnija rada iespaidu, ka marka izkūst ūdenī.

Martas dāvanas – vairāki melnbalti mākslas fotouzņēmumi, visticamāk, no piezīmju bloknota, uz kura lapām vēstule rakstīta.

Lewis Buzbee – Migla, atmiņas un jūras tuvums

Lewis raksta no Kalifornijas, kur jūra nekad nav tikai fons – tā ir vējā, miglā, pašās ielās. “Mana mīļā Jūra,” viņš iesāk, un jau no pirmās rindas jūtams, kā ar katru teikumu padziļinās viņa mīlestība uz to. Viņš neraksta tikai par savām atmiņām, un prāto, vai arī jūra spēj atcerēties mūs? “Tu šķieti pietiekami plaša, lai spētu to darīt, atcerēties.”

Viņš atceras bērnības ūdeņus – bradāšanu pie Kīvestas, kur Atlantijas okeāns satiekas ar Karību jūru, kā tētis un brālis ķer jūras veltes vakariņām. Tagad viņa krasts ir Klusais okeāns Sanfrancisko, un viņš bieži dodas līdz Okeāna pludmalei kopā ar sievu un meitu. Jūra piesātina viņa dzīvi, veido viņa elpu, domas, piederības sajūtu.

Viņa vēstulē nav distances – ir tikai klātbūtne. Pat atrodoties dziļāk sauszemē, viņš raksta par sajūtu, ka jūras prombūtne viņu vajā, it kā pārāk ilgs laiks prom no tās šķīdinātu viņa pamatus. Migla kļūst par paša ūdens metaforu, kas ieveļas pilsētas ielās kā atgādinājums: jūra vienmēr ir tepat. Lewis jūra nekad nav tālu – tā dzīvo viņā, klusi un nepārtraukti.

Aploksne ir balta un klasiska.

Zane Iltnere – Jūra kā brīvības rotaļu laukums

Zanes vēstule sākas ar atmiņām par ezeru, kas smaržo pēc ūdensrozēm un saulē sasilušas gumijas laivas. Tomēr tieši Baltijas jūra ir tā, kas rada brīvības sajūtu. Viņa atceras bērnību, kad ar plaši atvērtām acīm nira dzidrajos viļņos kopā ar citiem bērniem. Viņi spēlējās zem ūdens kā palēninātā filmā – ķermeņi viegli un plūstoši, un jūra sniedza ne tikai telpu, bet arī atļauju – rotaļāties, izzināt, piederēt.

Viņas vārdos ir prieks un pārliecība, ka jūra vienmēr nozīmējusi atbrīvotību un rotaļu. Pat ziemā, kad jūra līdz horizontam aizsalusi balta, viņa kopā ar citiem iet pa to, un kad kāja izlauž ledus virskārtu, mirklī nonāk te un tagad.

Zanes vēstule ir pilna kustības un mīļuma: gara, rotaļīga deja ar un gar jūru, kas aptver tik dažādās Latvijas pludmales – Jūrkalni, Vitrupi, Kolku. Viņa raksta nevis ar nostalģiju, bet ar pateicību – par jūru, kas nekad nav vienāda, un tomēr vienmēr viņu pieņem atpakaļ un nav salīdzināma ne ar vienu siltzemju jūru.

Aploksne ir balta un klasiska ar Latvijas tautastērpu pastmarku.

Dāvana – fotogrāfija ar saules izgaismotiem smilšu viļņiem.

***

Nākamās septiņas vēstules publicēšu nākamtrešdien. Vai Tava jau ir gatava? Es ticu, ka Tev ir stāsts, ko pastāstīt jūrai. Iedošu pastkastes adresi: beachbooksblog@beachbooksblog

Anna

Jūras bibliotekāre

Leave a reply to 011: A Letter to the Sea – SEA LIBRARY BOOKS Cancel reply